I was relaxing one day in my armchair when a message pinged on my phone. It was from an acquaintance who sent me a lengthy WhatsApp message along with multiple photos of his blood test results and an ultrasound scan. He had just been told that he has fatty liver disease, is pre-diabetic, hypertensive, and has significantly abnormal cholesterol levels. I glanced through his message, examined his blood results and ultrasound report, and fully agreed with his primary care doctor. I had only recently met this person a few times, but I learned quite a bit about his background. On one occasion, he confided in me about how tired he feels every day. He experienced mood swings and felt so depleted of energy that there was no time to exercise. He works a stressful 9-to-6 job with irregular eating habits, sometimes snacking on power bars to get through the day. He sleeps poorly and drinks energy drinks to boost his energy levels so he can get through his daily work.

Does this sound familiar?

Sadly, this is the fast-paced world we live in, where stress is high, ultra-processed foods are easily accessible, everything seems designed to encourage a sedentary lifestyle, sleep is undervalued, and exercise is almost non-existent. Life feels like a rat race where money and power take precedence, and our health is often neglected. The acquaintance mentioned earlier is just one of many patients who come to me with a letter from their general practitioners or family medicine specialists reporting the same issue. All of them have no symptoms and are simply there for their mandatory annual health checks, but get caught up by blood readings that are somewhat ‘off’.

This brings us to another common gastroenterology topic, where I want to focus on a profound issue that has a significant impact not just on our country, but on the world.

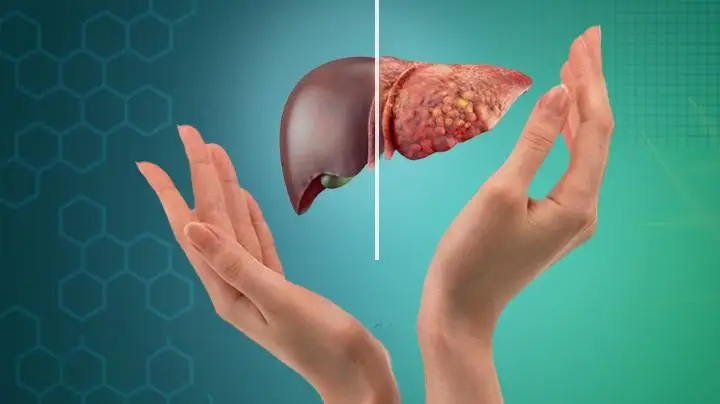

Figure 1: An illustration depicting a transition between a normal liver (left) and a hardened (cirrhotic) liver (right) (image courtesy of the Gleneagles Hospitals India website).

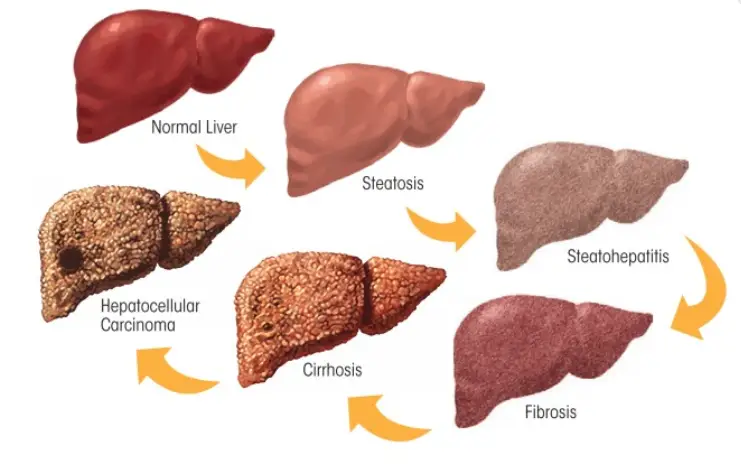

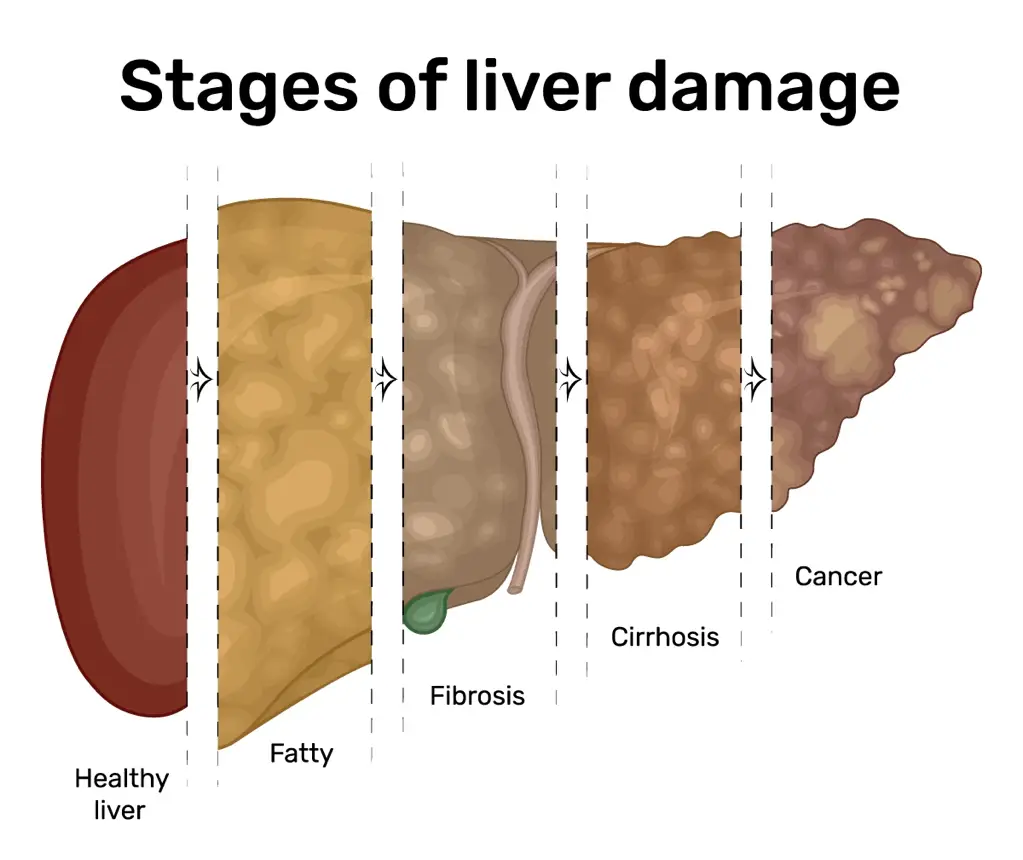

Fatty liver disease, medically known as hepatic steatosis, is a condition characterized by the accumulation of excess fat in the liver cells. While a small amount of fat in the liver is normal, when fat constitutes more than 5-10% of the liver’s weight, it becomes a health concern. Fatty liver disease can be benign in its early stages, but if left untreated, it may progress to more serious liver conditions, including inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, or even liver cancer.

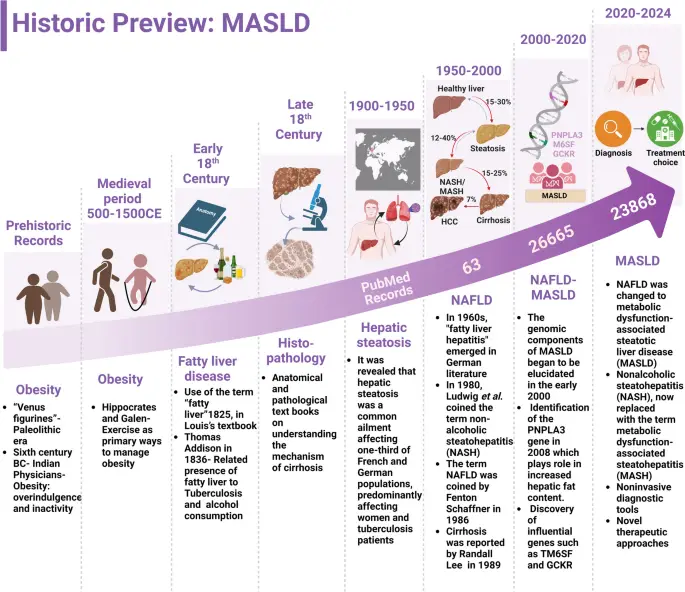

Figure 2: Historical progression and key milestones of fatty liver along with medical advances in diagnostics and therapeutics from prehistoric times to modern science (image courtesy of Gurjar et al. Lipids in Health and Disease 2025).

There are two primary types of fatty liver disease:

Figure 3: Fatty liver is part of a bigger dysfunctional metabolic syndrome, with the most typical culprit being overweight and obesity (image courtesy of mydiagnostics.in website).

Figure 4: Although the underlying mechanisms differ, both alcohol and fatty liver progress similarly in terms of subsequent complications (image courtesy of Dr Kiran Peddi’s website).

Each type can progress to a more dangerous condition called steatohepatitis—either metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) or alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH)—which includes inflammation and liver cell damage along with fat accumulation.

Figure 5: The natural progression of liver inflammation caused by fatty liver. All other causes of prolonged or chronic liver inflammation follow a similar pathway, ultimately leading to either liver cirrhosis or liver cell cancer (image courtesy of the Midas Hospital website).

Although the exact mechanisms leading to fatty liver are not fully understood, several risk factors have been identified.

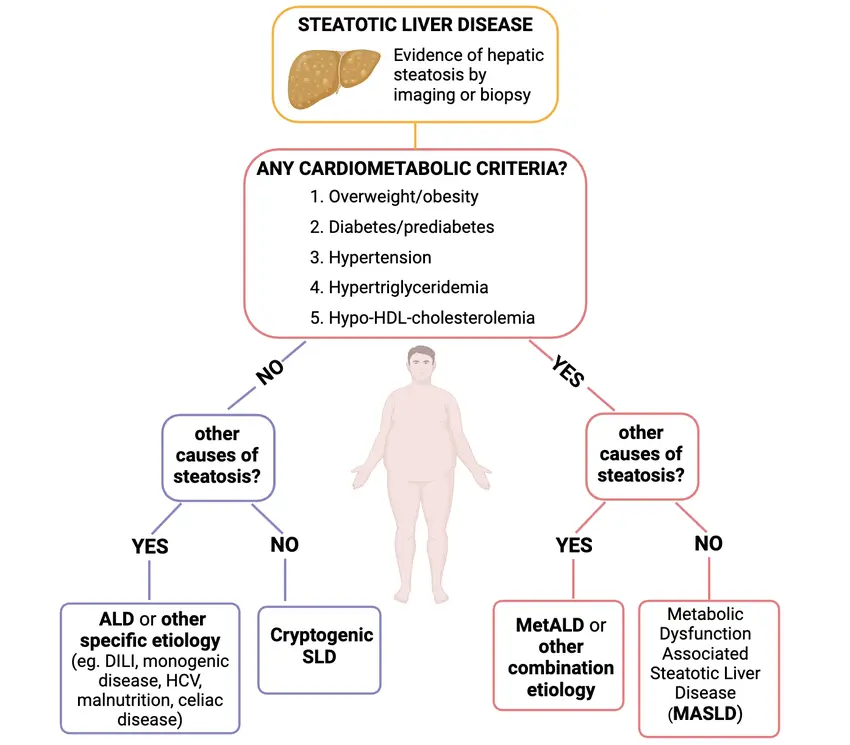

Figure 6: Simplified workflow cheat sheet for doctors encountering patients with fatty liver – the first step is to identify the presence of cardiometabolic criteria (any one of five existing in a patient is sufficient). The second step, if the answer to having such cardiometabolic criteria is yes, is to distinguish between alcohol liver disease and MASLD. Generally, thorough history taking and assessing the amount of alcohol consumed will help differentiate between MASLD and AFLD.

The primary cause of AFLD is chronic, excessive alcohol consumption. The liver processes alcohol, and when intake exceeds its capacity, fat accumulates.

Other risk factors include poor nutrition, chronic viral hepatitis B & C infection, ongoing use of unlicensed herbal and dietary supplements, autoimmune liver diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis), certain heart and blood vessel conditions (cardiac cirrhosis and Budd-Chiari syndrome), and specific genetic predispositions (hereditary haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

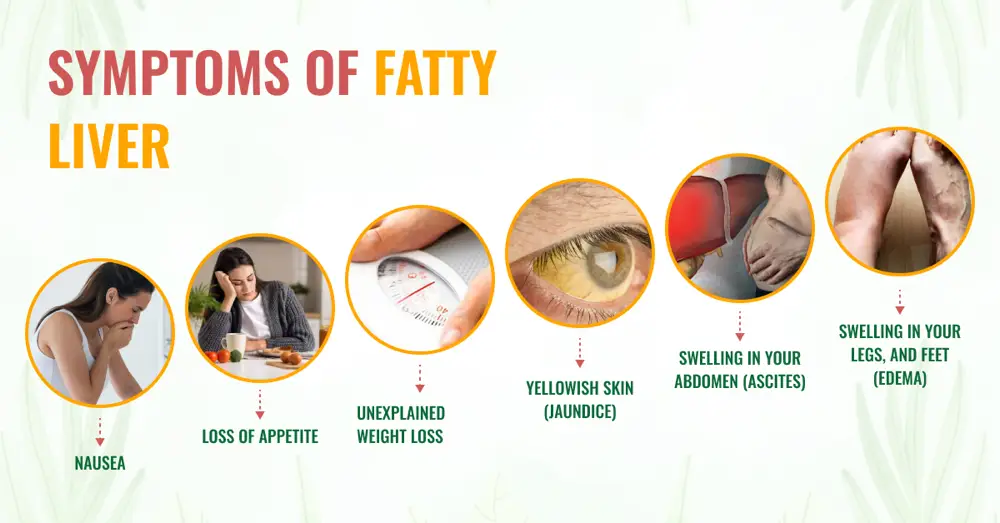

Fatty liver disease is often called a "silent" disease because most people do not experience symptoms, especially in the early stages. When symptoms do occur, they may include:

Figure 7: Common symptoms encountered in patients with fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and liver cirrhosis (image courtesy of the Hospital and Institute of Integrated Medical Sciences website).

As the disease progresses to more severe stages like MASH or cirrhosis, signs may include:

Since symptoms are often absent, fatty liver is frequently discovered incidentally through routine blood tests or imaging studies done for other reasons.

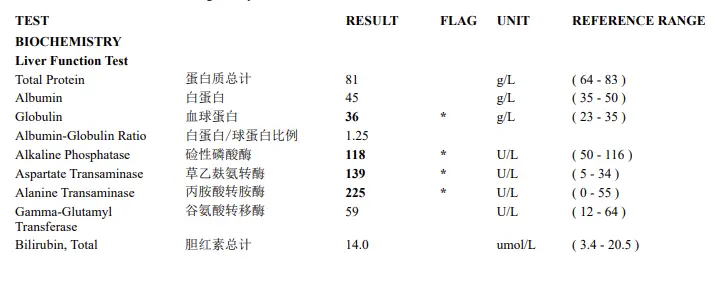

Figure 8: Commonly encountered liver function derangement in patients with MASLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH).

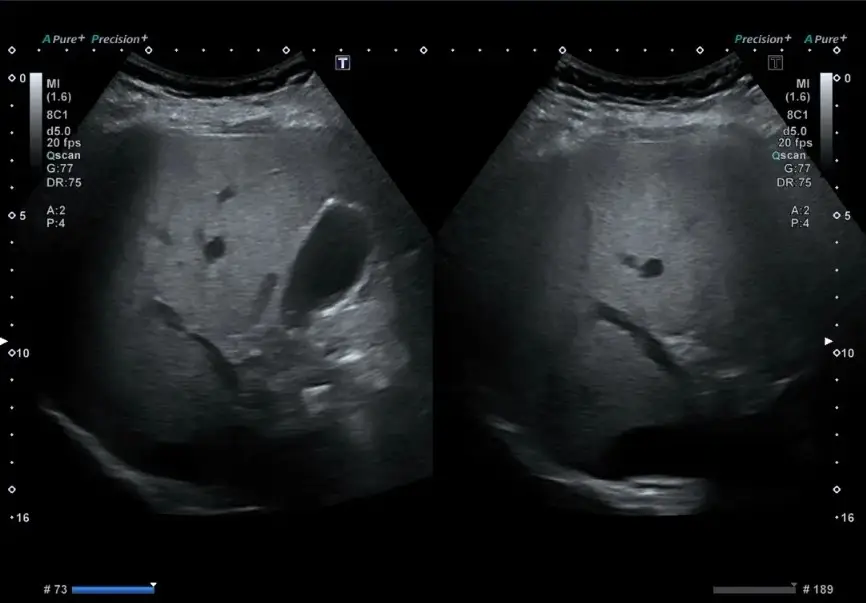

Figure 9: An ultrasound of a patient with MASLD. Common findings include an enlarged liver, increased brightness due to the presence of fat droplets within the liver cells, and blurring of the blood vessel and ductal appearance.

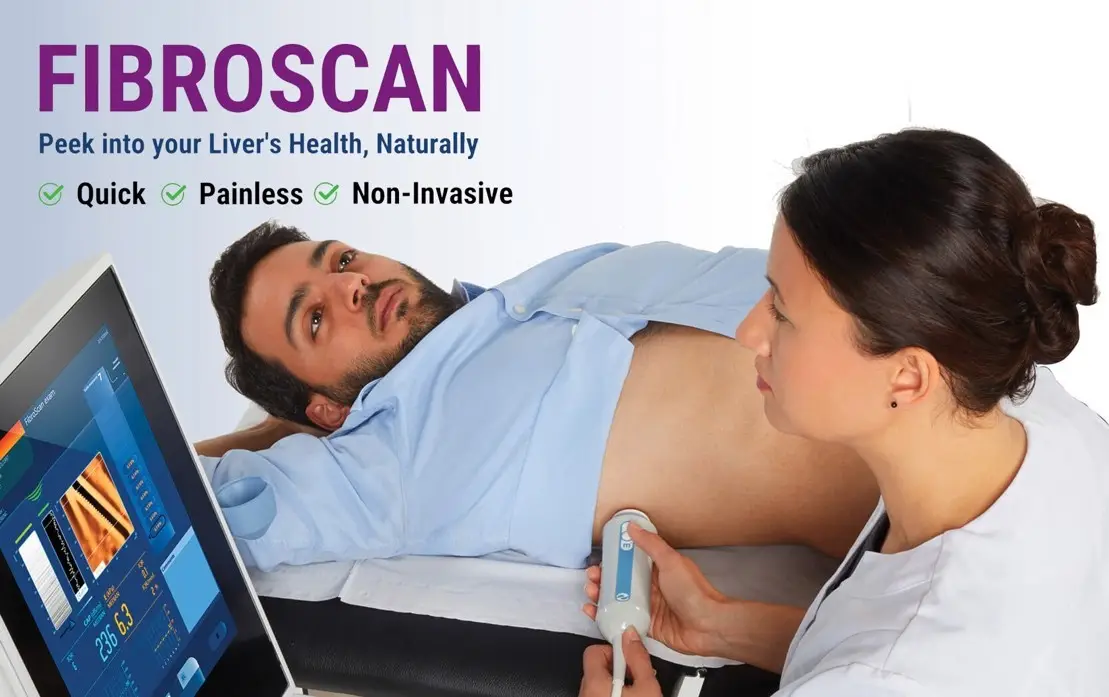

Figure 10: Similar to an ultrasound, the Fibroscan collects data on liver stiffness and provides readings that are easy to interpret regarding the degree of liver scarring (image courtesy of the Fibroscan website).

While simple fatty liver (steatosis) usually does not threaten liver function, it can progress to:

Figure 11: The stages of liver disease progression begin with fatty liver, characterised by fat build-up and little or no inflammation or liver cell damage. As inflammation persists, further damage ensues, leading the liver to enter the stage of worsening fibrosis before advancing to cirrhosis. Decompensated cirrhosis is the most severe phase, where the liver’s ability to sustain normal function is greatly compromised, markedly increasing the risk of serious complications (image courtesy of the Aurora Health Care website).

Currently, no medications are specifically approved for treating fatty liver disease. The cornerstone of management is lifestyle modification:

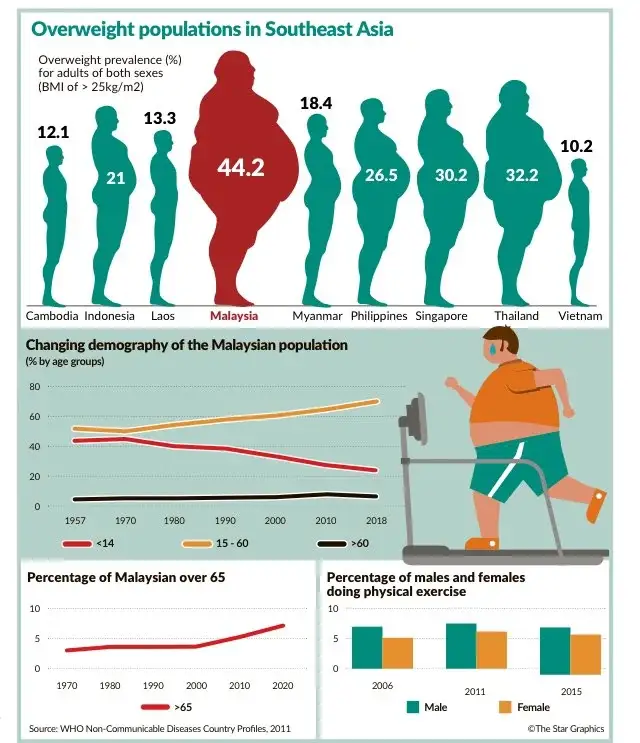

Figure 12: Malaysia is ranked as the most obese nation in South East Asia, and, unsurprisingly, we recorded the highest cases of fatty liver along with other cardiometabolic risk factors. Overnutrition caused by food excess, poor awareness, a highly sedentary lifestyle, and physical inactivity are key factors behind these alarming figures (image courtesy of Reddit).

Figure 13: Include more greens, fibres, fruits, and vegetables in your daily meals. Avoid processed and ultra-processed foods from fast food outlets and convenience kiosks. Cooking methods help reduce calories, so opt for dishes that are boiled, grilled, broiled, charbroiled, stir-fried, or steamed, and reduce oily and greasy foods. Seek advice from a dietitian if you need more information about your dietary choices (image courtesy of the Integral Wellness UK website).

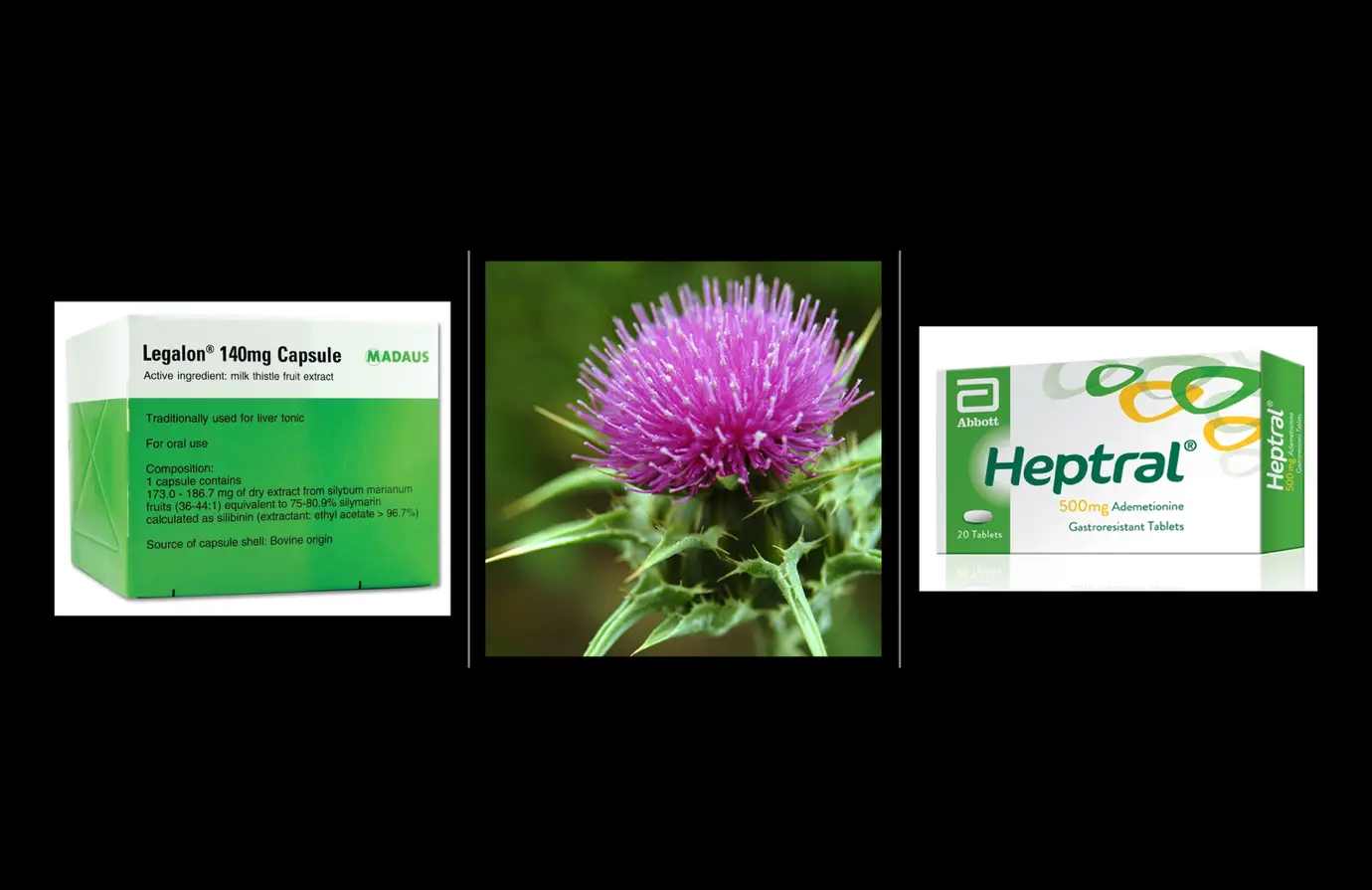

Some patients with advanced disease or specific complications may require medications such as insulin sensitizers, vitamin E, or lipid-lowering agents; however, these are only used under medical supervision. In rare cases of liver failure, a liver transplant may be considered. Liver antioxidants are widely available, and those approved for use include SAMe (Heptral) and milk thistle extract (Legalon).

Figure 14: Sample boxes of Legalon (with milk thistle for illustration) and Heptral (active compound – ademetionine, a naturally occurring antioxidant found to be diminished in patients with fatty liver or chronic liver diseases).

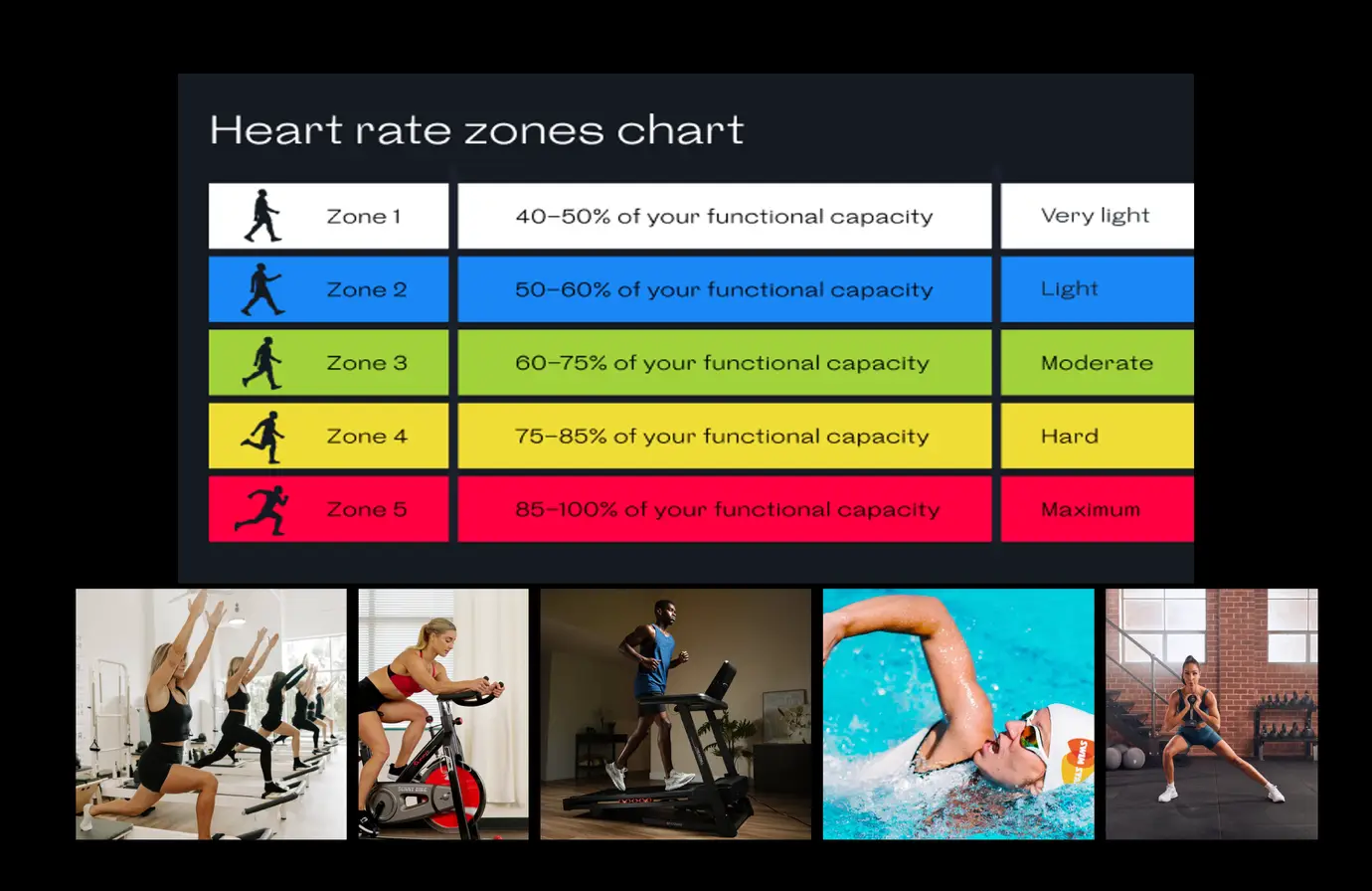

Figure 15: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle through physical activity can take many forms – a weekly mix of cardio and strength training at a moderate intensity is recommended. By keeping your heart rate within Zone 2 to 3, you sustain efforts within a manageable range to develop a lifelong exercise habit. Start slowly, and then build from there as you become stronger. Avoid jumping in too quickly or overdoing it, as the goal is to create a long-term outcome, not just a short-lived one (image courtesy of Sunny Health, Swim Stars, Welltory.com, Body Bar Pilates, Sweat, and 220triathlon.com websites).

Prevention of fatty liver disease centers on maintaining a healthy weight, engaging in regular physical activity, eating a balanced diet, moderating alcohol consumption, and managing risk factors such as diabetes and high cholesterol.

The outlook for individuals with fatty liver disease varies. Those with simple steatosis often live normal lives if they address underlying risk factors. However, if the disease progresses to MASH, cirrhosis, or liver cancer, the prognosis becomes more serious. Early detection and intervention dramatically improve outcomes.

Fatty liver disease is an increasingly common condition worldwide, paralleling rising rates of obesity and diabetes. It can be silent for years, yet it carries the risk of serious liver damage if unaddressed. The good news is that, with proper lifestyle changes and medical management, most cases can be improved or even reversed. Regular checkups, healthy habits, and awareness are key to protecting your liver health and overall well-being.