Heartburn, more commonly known as 'GERD' (gastroesophageal reflux disease) to the local community, happens when contents from the stomach, specifically acid, back up into the food pipe. Before proceeding, it is essential to understand a few key terms and anatomical positions to comprehend this common ailment.

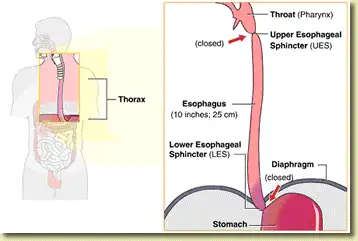

Figure 1: Important landmarks of the esophagus, specifically the location of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) (image courtesy of the Endoscopy Center of Monroe).

Firstly, the food pipe that connects the back portion of our mouth to the stomach is known as the esophagus. The esophagus is a long muscular tube that aids in channeling food and liquids into the stomach. The act of swallowing is voluntary, whereas the propelling of food into the stomach is an involuntary one. Two valves guard the esophagus – the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), located at the top of the esophagus, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), located at the bottom of the esophagus. We will primarily focus on the LES, as it is a key landmark responsible for the development of heartburn. Both of these sphincters are composed of muscular rings that open and close at specific intervals to permit the entrance of food and prevent contents from regurgitating. When one or both of these sphincters do not operate normally, we get stomach contents – be they acidic or non-acidic refluxing upwards and causing symptoms of heartburn.

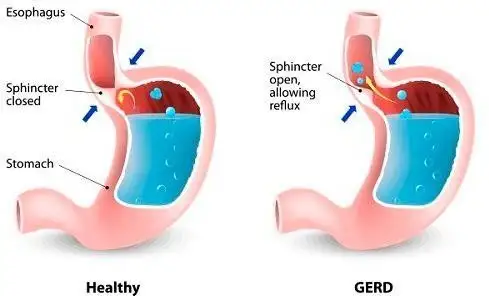

Figure 2: Diagrammatic representation on the function of the lower esophageal sphincter in preventing stomach contents from backing up into the esophagus (image courtesy of Health tips by Teleme).

Now that we are familiar with the landmarks of the esophagus let us take a moment to appreciate how common heartburn is among the global populace. Heartburn symptoms are common, and about a quarter of people experience them at least once a month.

Having developed a one-off episode now and then does not translate to having GERD, as the latter is a terminology reserved for individuals who have more frequent symptoms that would require additional medications to obtain relief. Heartburn, as common as it is, can occur after a hefty meal, mainly if it contains fried and greasy food or after lying down immediately after eating. It can also be triggered by certain medications that relax the LES more than it is designed to. Certain foods may also precipitate heartburn by either increasing the acidity of the stomach content or relaxing the sphincters more.

On the flip side, GERD is a more established condition that would not easily go away. About a fifth of the US population is afflicted by GERD, primarily because of associated risk factors such as obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Other risk factors that precipitate GERD include being male and over 50 years of age. Closer to home in Malaysia, it was reported that around 10% of patients experienced monthly heartburn, whereas 6% would go on to develop weekly symptoms. Based on this data set published almost two decades ago, the prevalence was already considered high in our country. With the progressive rise in the trend of obesity afflicting Malaysia and the fact that obesity is a well-known risk factor for heartburn and GERD, we can only imagine how the incidence has exponentially grown over the years.

Interestingly, a community-based study discovered that ethnicity may play a role in the prevalence of heartburn, with Indians reporting more symptoms compared to their Chinese and Malay counterparts. The likeliest cause for such disparity remains debatable. However, local environmental factors, such as cultural norms, social practices, dietary habits, and lifestyle choices, may play a significant role.

The classical symptoms for heartburn begins with a burning sensation in the upper part of the abdomen known as the epigastrium. The burning feeling is then referred upwards in the middle part of the chest, where patients may describe a sensation of chest tightness, chest pains, and a subjective sense of difficulty in drawing in deep breaths.

There can also be associated increased in salivation (known as water brash), a sour taste at the back of the throat (acid brash), dry throat, throat irritation, sore throat, prolonged cough, and halitosis. Heartburn symptoms often occur after consuming heavy meals, particularly those rich in fat and protein, and are exacerbated when lying down immediately after eating. An overfilled stomach makes its contents far easier to regurgitate back into the esophagus, aggravating symptoms of GERD. Hence, one of the common advises given to mitigate heartburn is to eat small frequent meals, avoid eating four hours before sleep, prop up the head end of your bed when sleeping, and lying on your left to let gravity pull the stomach content away from the LES.

Figure 3: Symptoms and signs of heartburn in a cartoon illustration (Image courtesy of the Australia Wide First Aid website).

Severe and chronic heartburn may also contribute to dental caries, sinus problems, and even middle ear infections (otitis media). Some patients may even feel a lump or tightness in their throat and fail to clear it through coughing and retching. This tightness is known as ‘globus pharyngeus’, or simply globus, and is believed to be caused by tense muscles surrounding the throat.

Heartburn is commonly associated with a condition called functional dyspepsia, where patients experience early satiety or a feeling of fullness too soon during a meal. They can also complain of frequent belching and burping, abdominal bloatedness, abdominal discomfort, and frequent chest and abdominal heaviness. Functional dyspepsia in this category of patients results from the failure of the stomach muscles to relax and accommodate incoming food, thereby increasing the likelihood of acid reflux. Nausea and vomiting are very infrequent in cases of heartburn and functional dyspepsia and usually point to another problem altogether.

It's important to note that certain symptoms require urgent medical attention in cases of heartburn. These symptoms are classed under red flag symptoms and would include difficulty and painful swallowing (dysphagia and odynophagia), weight and appetite loss, vomiting blood, and passing blood in the stools. If you're experiencing any of these symptoms, don't hesitate to seek medical advice. Your health and well-being are our top priority, and we're here to help you navigate through these challenges.

Figure 4: Caffeinated beverages, certain tea, alcohol, chocolate and cocoa products can lead to heartburn symptoms. Watch out also on the type of additives that you put into what may seemingly look like an innocent heartburn-free drink as there are certain compounds that can still increase acidic production, irritate the esophageal lining, and relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter.

The majority of patients suffering from persistent heartburn are often aware of certain foods that trigger their symptoms and try their best to either reduce or eliminate them from their meals. These foods and beverages include coffee and certain caffeinated teas, chocolates, alcohol, cocoa products, carbonated drinks, tomatoes, fatty or spicy foods, and citrus fruits (such as oranges, pineapples, mandarins, tangerines, limes, lemons, starfruits, and grapefruits). Caffeine is a well-known substance that contributes to heartburn by relaxing the LES and also promoting stomach acid production. By itself, coffee is naturally acidic and may irritate the lining of the esophagus, which is bathed in an alkaline environment.

Mint-based teas, such as spearmint and peppermint, also work through a similar mechanism by relaxing the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), thus increasing the likelihood of acid reflux. Sometimes, it may not be the tea alone, as choices of weakly acidic tea are plenty – it may just be the choice of adding a slice of lemon, a hint of peppermint, or cubes of sugar that need to be avoided. Having a food guide to the well- known heartburn precipitants helps patients make informed choices about their daily meals. However, some individuals may be more susceptible to other foods not listed here.

Figure 5: Avoiding citrus and acidic fruits, spicy, fatty, and greasy/oily foods helps to alleviate and avert symptoms of heartburn and in cases of GERD, such dietary avoidance reduces breakthrough episodes.

Having described the types of food to cut down on or avoid, we also need to consider the cooking style. Regardless of ethnicity, Malaysians generally adore spicy and fatty foods. Deep-fried, double-fried, rendang, curry, or even dishes whipped with loads of onion and garlic may trigger an attack of heartburn. Aside from being acidic (such as onions and garlic), oily and greasy foods stay longer in the gut and take longer to digest. Higher 'fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols' diet (or FODMAP diet for short) is another class of food compound that is hard to absorb in the small bowels thus leading to fermentation and gas formation.

As a consequence, patients would develop symptoms of bloating and gassiness, which may sometimes lead to abdominal distension and precipitate the frequency and severity of heartburns. Examples of high FODMAP foods include onions and garlic. However, it is not recommended to fully adopt a FODMAP diet without first consulting your doctor, as they are not a formal part of managing heartburn and GERD.

Moving from the culinary subject and into lifestyle choices and activities that may lead to heartburn, patients are constantly advised to lose weight, stop smoking, and drink alcohol in moderation.

The era of modern living, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and, in the near future, the increasing use of assistive robotics has made things far more convenient. With the push of a button or a mere flick of a switch, operations of any field can be completed in mere seconds. Coupled with the numerous availability of processed foods leading to physical inactivity and over-nutrition, it is no surprise that globally, we are contending with the obesity pandemic. Life is definitely easier!

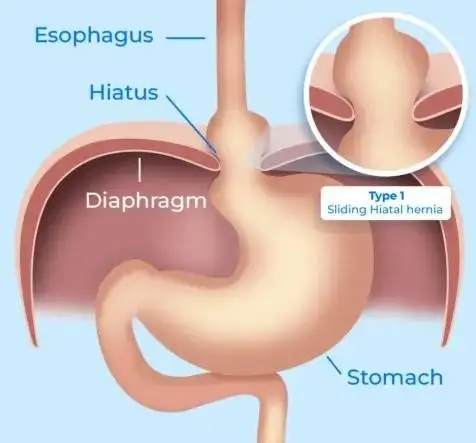

Figure 6: The diaphragm muscle plays a central role in the LES muscle apparatus – a weakened diaphragm increases the chances for a hiatal hernia to form. This cartoon demonstrates the rolling of the top part of the stomach into the chest cavity, above the diaphragm (image courtesy of Dr Gabriel Arevalo MD’s website).

Being overweight or obese increases the girth of the abdomen and the intra-abdominal pressure, which, as a result, limits the stomach's expansion capability and potentially lowers the threshold for the backflow of acidic contents into the esophagus. If contents can't move forward, they move backwards and follow the path of least resistance. The LES, now faced with the increased abdominal pressure, weakens further, permitting the upper part of the stomach to roll upward into the chest cavity, above the diaphragm (muscle separating the chest from the abdomen and plays a crucial role in forming the LES muscle apparatus), hence creating what is known as a hiatal hernia. The barrier created by the LES is now lost. The top part of the stomach, which is known to harbor acid-producing cells (parietal cells), would freely bathe the lower part of the esophagus with acid, further increasing the risk, severity and possibly complications of heartburn and GERD.

Figure 7: The impact of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption is tremendous in the central mechanism of worsening heartburn symptoms, precipitating GERD, and increases the risk of GERD-related complications such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer (image courtesy of City of Hope website).

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of heartburn by further relaxing the LES, stimulating more acid production, and reducing saliva production, the latter of which is crucial in buffering stomach acid. Along with the UES and LES, saliva is an innate defense mechanism against acid refluxate. Smoking can damage the salivary glands, while nicotine can increase the viscosity of the saliva produced, thereby reducing adequate salivary flow. When this happens, the decreased production of saliva and the

thickened saliva density can no longer perform their role optimally, preventing a person from clearing the regurgitated acid through swallowing.

Alcohol consumption could also precipitate heartburn-related symptoms, much like that of cigarette smoking. Though interestingly, there are indirect mechanisms that may worsen things further when alcohol ingestion is taken in excess. Oftentimes, alcohol is not just taken alone but in combination with snacks or fried/oily foods to delay stomach emptying and, hence, slow down alcohol absorption and intoxication. Even cocktails, or mixers that are now a favorite among society are laced with pop soda (carbonated drinks) and sugar, which, as already described above, are known precipitants of heartburn.

Given that dietary and lifestyle choices can impact both heartburn and GERD, it is crucial to educate patients that slow but progressive changes, such as weight loss through physical activities, dietary modification, smoking cessation and abstaining from alcohol, do wonders.

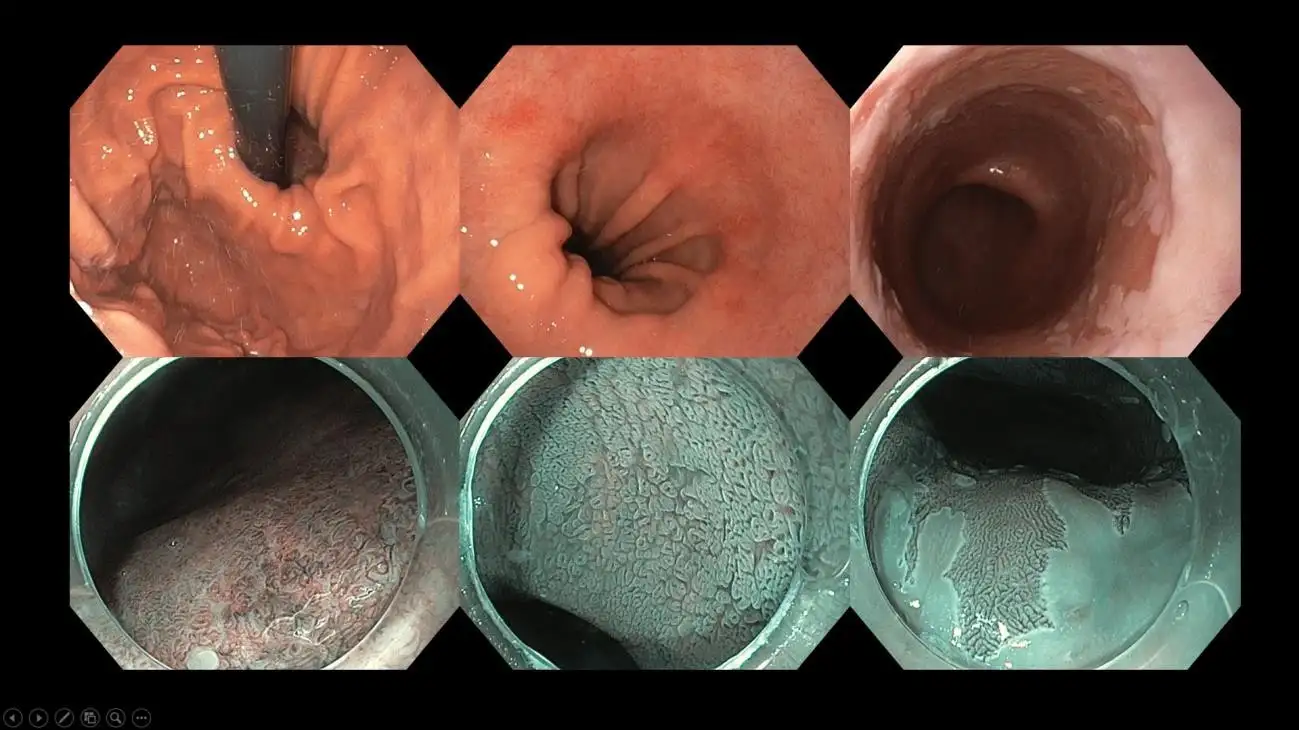

GERD-related investigations primarily involve upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, also known as endoscopy, to look for associated hiatal hernia, complications such as esophageal inflammation, Barrett's esophagus, and early or advanced cancers.

Endoscopy may also help identify other concomitant problems, such as Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and stomach cancers.

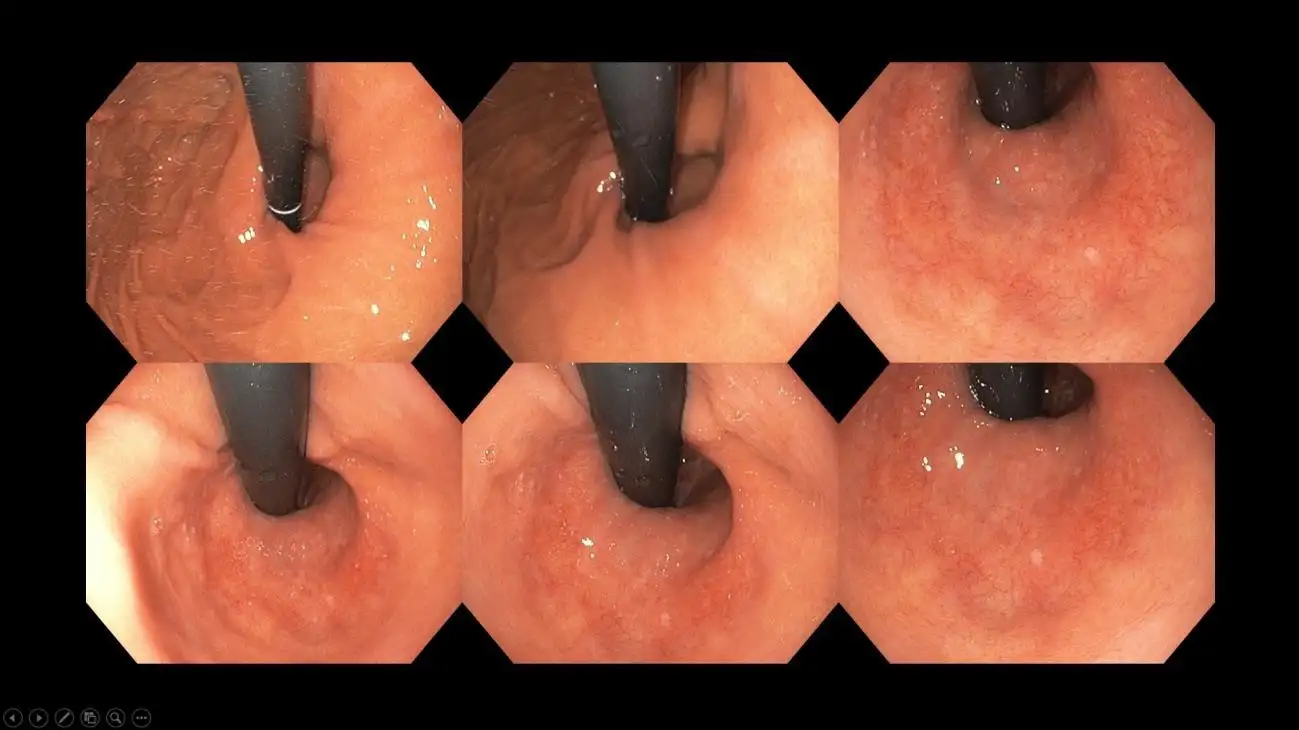

Figure 8: Appearance of a hiatal hernia – notice the large gaping hole surrounding the black tube which is the endoscope – a competent LES should engulf the scope leaving no to minimal gap in between.

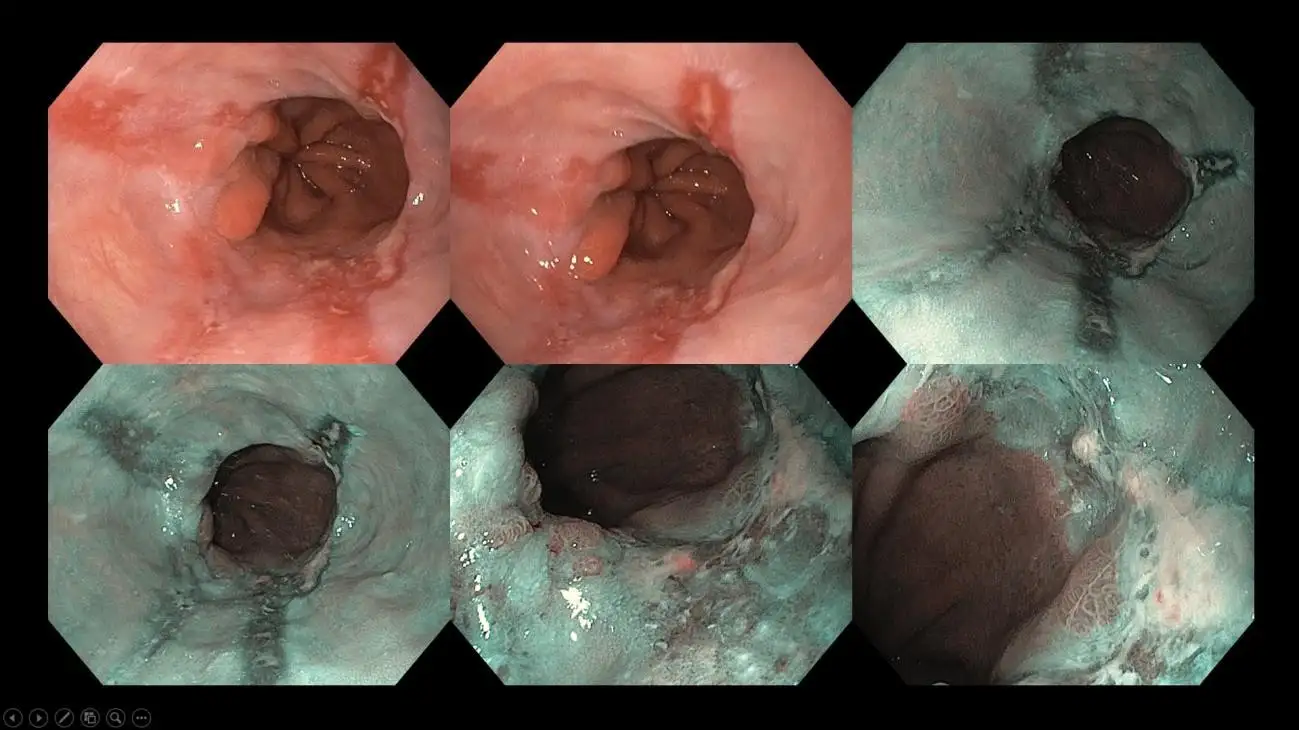

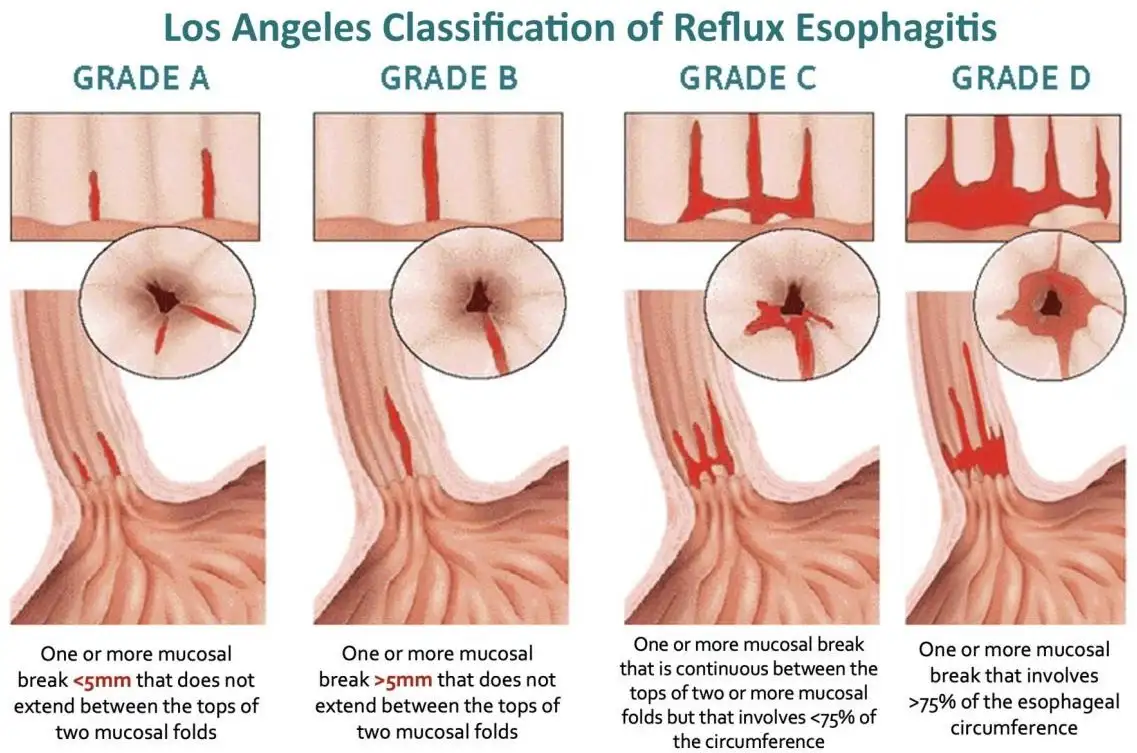

Figure 9: Inflammatory ulcers on the lower part of the esophagus as a result of chronic heartburn – these findings are called reflux esophagitis and are graded according to the length of the ulcer and circumferential involvement to guide subsequent choice of acid-suppressing agents.

Figure 10: The various grades of reflux esophagitis – doctors pay particular attention on these endoscopic findings and report them accordingly. Such findings serve to enhance the understanding of the severity of the underlying GERD, selection of treatment, evaluating response to treatment (either through monitoring symptoms or repeating an endoscopy) and patient counseling.

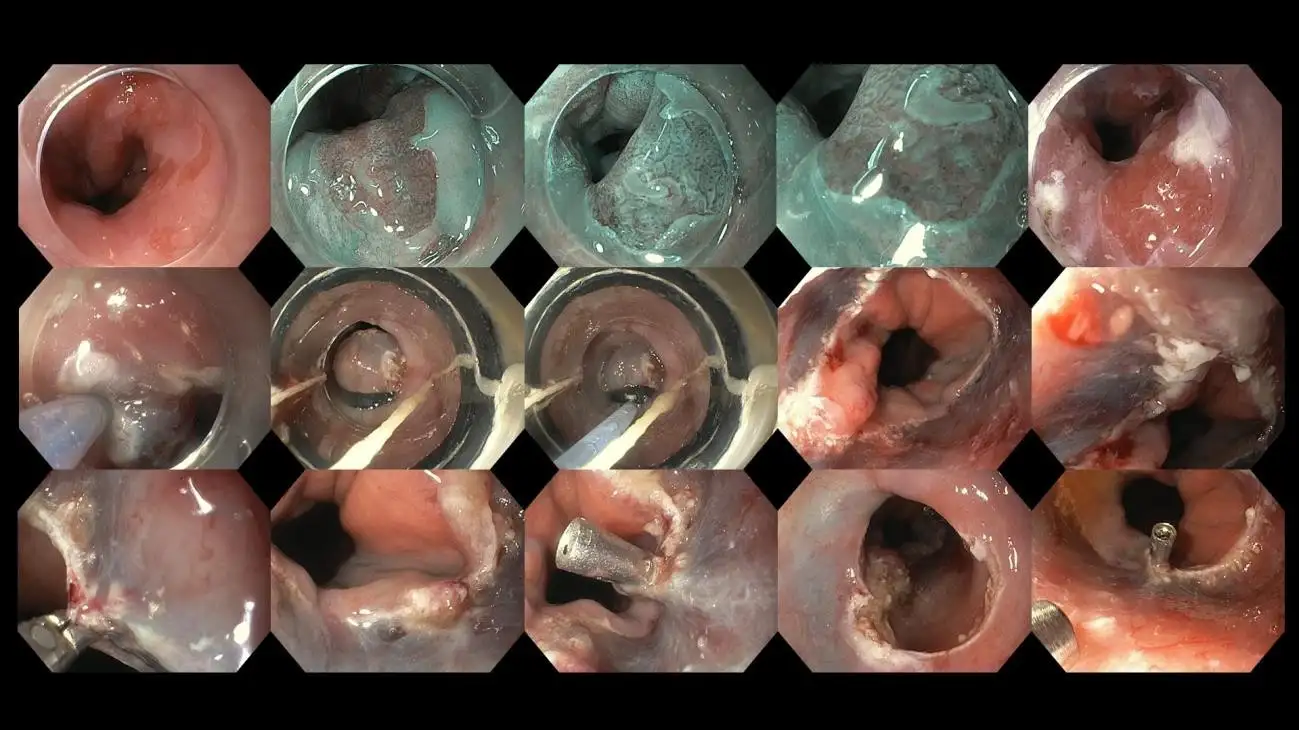

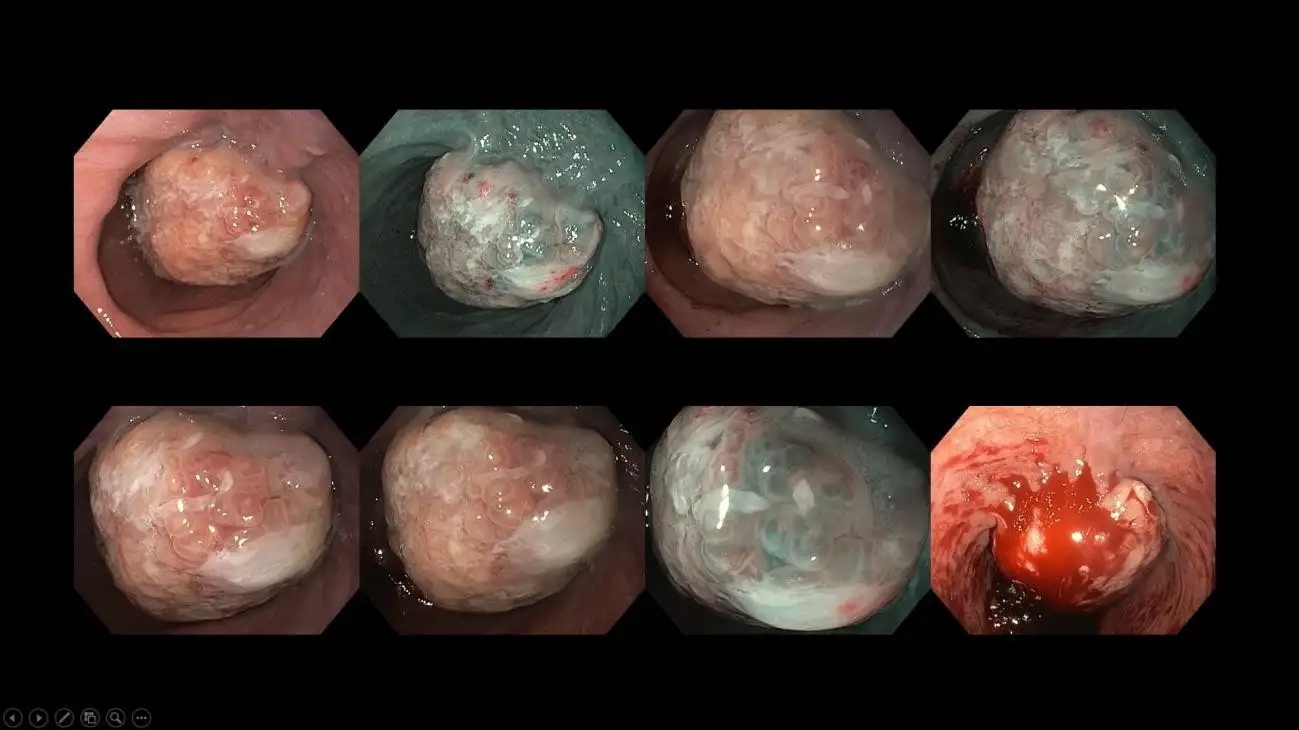

Figure 11: A patient with large hiatal hernia and Barrett’s esophagus – a specialized lining on the esophagus that heralds the potential risk of turning into esophageal cancer. In advanced imaging centers like ours, we perform image-enhanced endoscopy and dye-based chromoendoscopy with high-resolution endoscopes to carefully map out the extent of Barrett’s esophagus and look for suspicious areas that require biopsy and possibly, endoscopic removal. Some areas within the Barrett’s lining may harbor early cancer changes, and these imaging modality helps the endoscopist to target the area with precision.

Figure 12: Case of a patient with Barrett’s esophagus found to have pre-cancerous changes during detailed advanced imaging evaluation, currently undergoing endoscopic resection/excision. Endoscopic therapy is useful for early cancers that has yet to invade deeper layers of the esophageal lining as this offers a cure without additional treatment.

Figure 13: Case of an advanced esophageal cancer arising from a background of chronic heartburn symptoms. Such cases would require subsequent CT scan to look for metastatic spread followed by surgical and oncological consult. Often, a multidisciplinary board discussion will be held for these patients to discuss tailor-based management to provide the most optimal treatment and outcome for them.

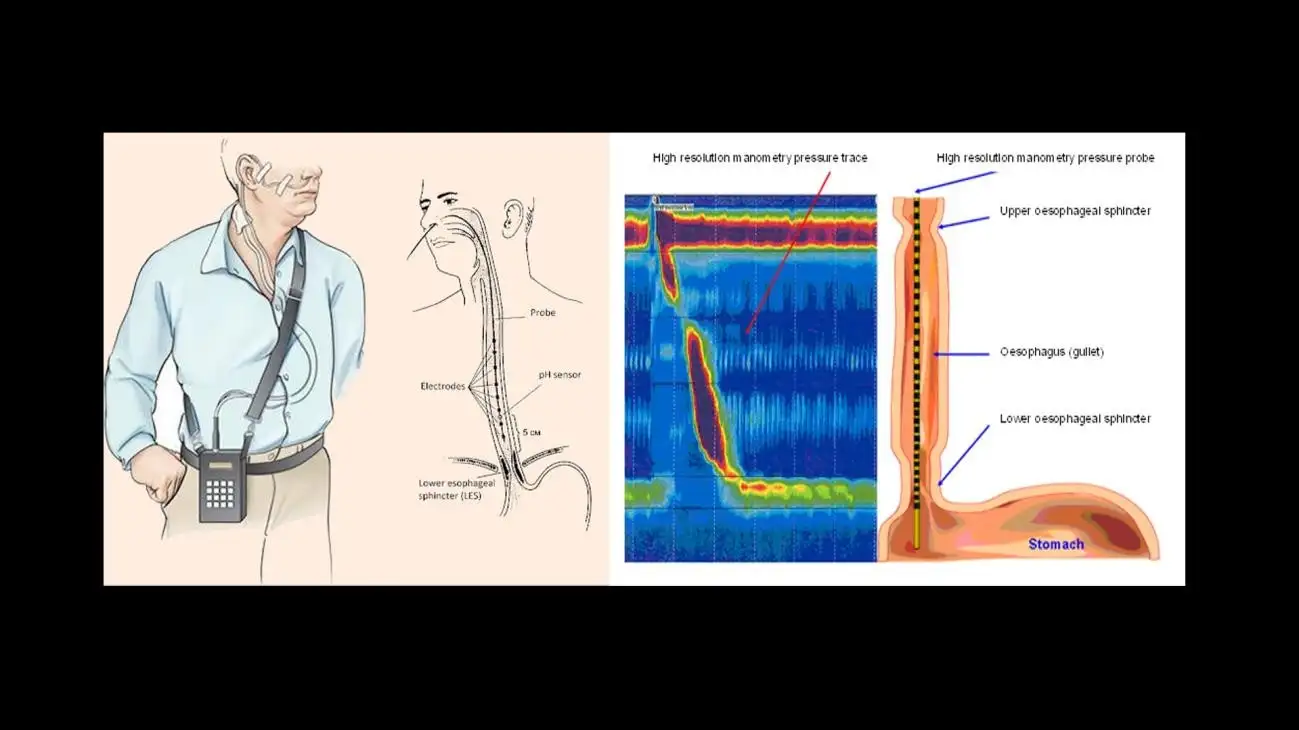

A more detailed study for GERD involves 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring and impedance study. Here, a thin, flexible tube is passed through your nose and positioned above the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to analyze the severity and frequency of reflux episodes. The patient would wear a small device on their belt or waist, which holds all the recorded data. At the end of the test, the wire is removed from the nose, and the data is uploaded into a designated computer with a special application to interpret the results. More modern wireless devices, such as the Bravo pH testing device, are also available, where the recorder is temporarily attached to the lower end of the esophagus. The pH monitoring offers a more accurate modality for diagnosing true GERD, as there are other variants of heartburn-related disorders to contend with, such as non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), esophageal hypersensitivity, and functional heartburn, a variant of the disorder of the gut-brain interaction (DGBI).

Figure 14: Figure illustration of the 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring (left) and high-resolution esophageal manometry (right) (image courtesy of Srushti Gastro & Liver Clinic and Hull University Teaching Hospitals websites).

In most instances, an esophageal high-resolution manometry would also be performed in a similar setting before the pH studies as a means to record the integrity, pressure and movement of the esophagus and its' sphincters. The manometry test is done to rule out coexisting esophageal motility disorders or secondary causes that may precipitate heartburn. Both the pH and manometry tests are crucial in affirming a correct diagnosis of true GERD as opposed to other esophageal disorders, as the management varies significantly. The latter is even more pertinent when surgery is considered for refractory GERD. You want to ensure that the objective of the surgery is truly for medication- refractory GERD and not something else that requires a different form of management.

Older methods for diagnosing GERD, such as the barium swallow studies, are used less often nowadays and are limited to centers without access to pH and manometry studies.

The management of heartburn is a combination of lifestyle modifications and medications. Many a time, patients are more prone to ease their heartburn attacks with over-the-counter drugs for convenience and to keep a move on with their busy lifestyle. It is pertinent to take a step back however, and ponder the discussion above, examining the compounding risk factors that one has which may aggravate heartburn rather than relying solely on medications.

Here is a summary of non-pharmacological management that I advise my patients:

Here is a list of pharmacological management options to support ongoing lifestyle and dietary changes.

The surgical and newer endoscopic management of heartburn and GERD is beyond the scope of this discussion and will be addressed in a separate article in the future.

It is pertinent to note, however, that complications of GERD and, in particular, Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer arising from this specialized esophageal tissue are not as uncommon as once thought. The disease spectrum is on the rise in Malaysia owing to obesity and other associated metabolic disorders. So, if you do have prolonged symptoms of heartburn and a nagging discomfort that does not go away, possess risks such as smoking and alcohol consumption, or even being overweight and in your fifth decade of life, do not hesitate to obtain a consult with your general practitioners, physician, or gastroenterologists.