Introductory figure: Gallbladder and gallbladder stones (image courtesy of the Awkward Yeti website).

Gallbladder stones, or gallstones, are a common health concern affecting millions of people worldwide. Their prevalence varies by region, age, sex, and lifestyle factors, but they are among the most frequent digestive system disorders. It is estimated that about 10–15% of adults in developed countries have gallstones, although many remain symptom-free and unaware of them. Gallstones are more prevalent in individuals over the age of 40, with the risk increasing as people age. Many individuals with gallstones never experience symptoms; these are referred to as "silent gallstones” and are often discovered incidentally during abdominal scans for unrelated conditions. Only about 20–30% of people with gallstones will develop symptoms or complications during their lifetime.

Catherine, a 23-year-old university student, presented to my clinic with a three-year history of abdominal pain that has slightly worsened over the past two weeks. She described persistent upper abdominal discomfort triggered after eating spicy foods and has since avoided such meals. Occasionally, when the pain becomes too prolonged and intolerable, she seeks over-the-counter remedies to relieve her symptoms. These medications include alginates (Gaviscon and Alucid), antacids (Cimetidine), and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as Omeprazole and Pantoprazole. A few days before her presentation, her pain worsened after dinner. Her colleague, who also has gastric issues, shared some medication with her — later identified as a potassium-competitive acid blocker (Vocinti). This medication provided relief, although not immediately; it took about an hour for her to feel comfortable.

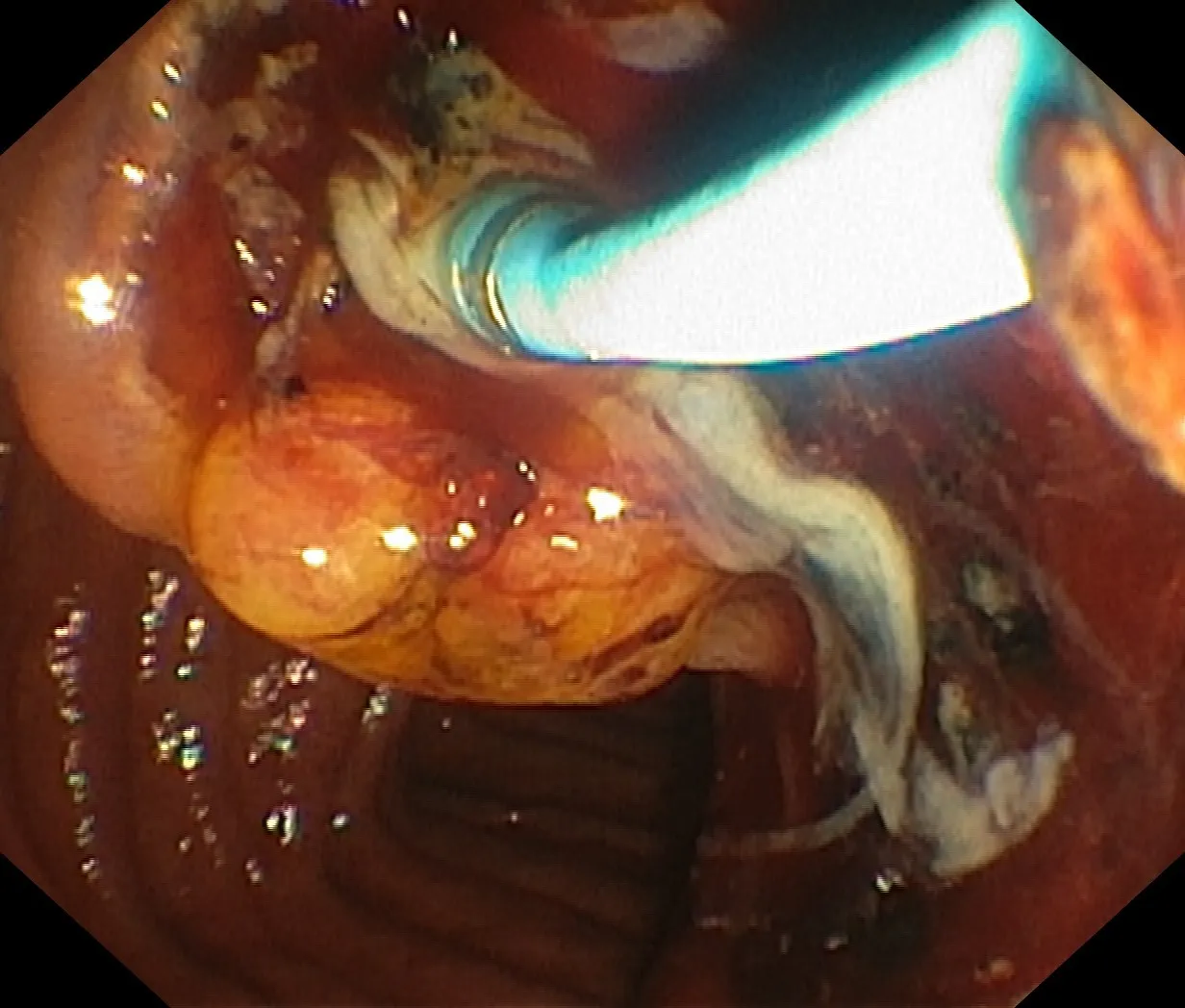

The following day, her pain returned, and although it was less intense than the day before, she decided to make an appointment to see me and be admitted for pain management and further assessment. Initial investigations, including a comprehensive blood test, were unremarkable, and an abdominal ultrasound revealed gallstones. Upon closer examination, there was no evidence of gallbladder inflammation. She chose not to wait for a urea breath test to exclude Helicobacter pylori infection, which could also cause similar symptoms, as she felt she could not discontinue her acid-blocking medications long enough to qualify for the non-invasive assessment. Therefore, she underwent an upper GI endoscopy, which was unremarkable. She was discharged three days later with a diagnosis of possible biliary colic, prescribed some PPIs, analgesics, paracetamol, and antispasmodic agents. She was also advised about functional dyspepsia and informed of potential triggers such as food and stress.

Three days after discharge, she returned late at night with severe abdominal pain following dinner. Due to the intense pain, she was readmitted for pain management. She had eaten a hot pot meal with her family, and while everyone else was well, she was not. This time, beside the abdominal pain, she also experienced a slight fever, nausea, recurrent vomiting, and loose stools. Her liver function tests showed significant abnormalities, with all her liver parameters elevated by more than 5-7 times the upper normal limit. A diagnosis of gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) and bile duct stone (choledocholithiasis) was suspected and later confirmed by an abdominal CT scan. She underwent an endoscopic procedure to remove the stone and was hospitalised for several days for intravenous antibiotics. An option for gallbladder removal was discussed, as many small stones remained inside the gallbladder, to prevent future episodes of stone-related complications. Although it took her some time to decide, the family and the patient ultimately agreed to proceed with the surgery to remove her gallbladder (cholecystectomy). She was discharged in good health and remained well throughout her follow-up until she was fully discharged from my care.

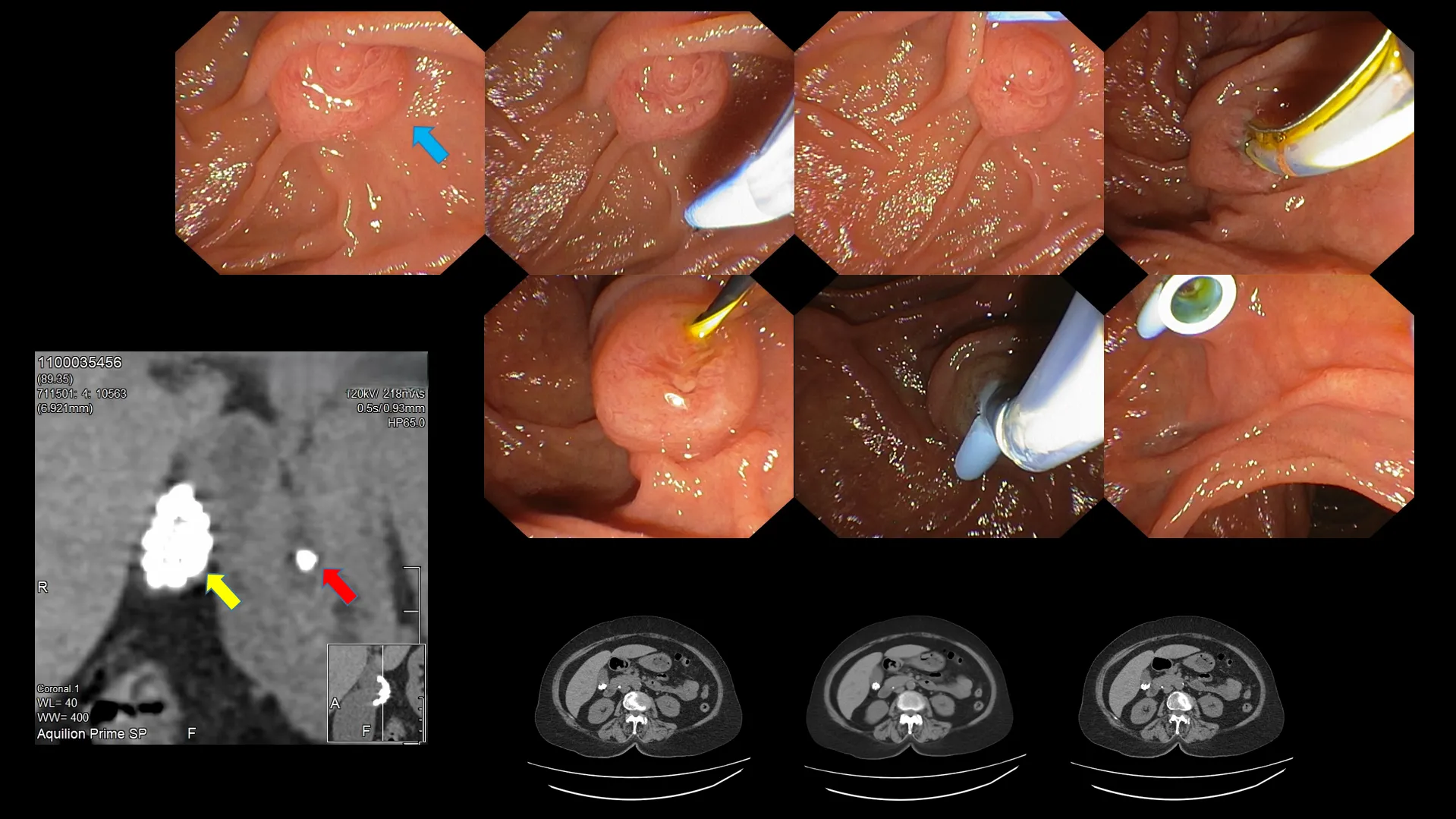

Hock Soon, a 44-year-old with a history of chronic diabetes and hypertension, was admitted after experiencing a week of severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, diarrhoea, and low-grade fever. His blood pressure was critically low at 80/40 mmHg, his heart rate was high at 160 bpm, and his oxygen saturation was 88% despite receiving supplemental oxygen. He was transferred to the ICU, given a stronger non-invasive oxygen device, and supported with three inotropic drugs to stabilise his blood pressure. Initial diagnosis suggested diabetic ketoacidosis, with elevated blood sugar (30 mmol/L) and high blood ketones (4.3 mmol/L). Treatment was initiated immediately without waiting for lab results. When the results arrived, his liver function tests and inflammatory markers were found to be significantly abnormal. An abdominal CT scan showed a large 2 cm gallbladder stone and a similarly large 2.5 cm stone within the mid common bile duct. Normally, the common bile duct measures less than 6-8 mm, so a 25 mm stone is massive and further aggravates the source of his ailment. The bile ducts above the stone were swollen due to blocked bile flow, resulting in severe illness caused by infected bile stasis. The diagnosis of cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis led my colleague to contact me for consultation. Within hours, an emergency ERCP was performed to decompress the biliary obstruction with a stent placement, but the stones were not removed at this stage due to severe infection and the risk of worsening his sepsis.

Hock Soon’s antibiotics were upgraded to ones that could effectively reach the biliary system, along with other supportive treatments. Over the next few days, he showed an incredible recovery, going from the brink of death to happily asking for his favourite food and drinks. He was then referred to our surgical colleague, who planned for him to have elective gallbladder surgery, stone removal, and bile duct reconstruction in the coming weeks. Fast forward three months, Hock Soon’s father visited me in the clinic for a different reason; since I discharged his son after the surgical team took over, I hadn't seen him since. His heartfelt gratitude truly touched me, as Hock Soon was his only son, whom he loved deeply. Moments like these remind me why I chose to be a doctor, and how ERCP, when performed with care and in proper conditions, can turn a potential tragedy into a life saved.

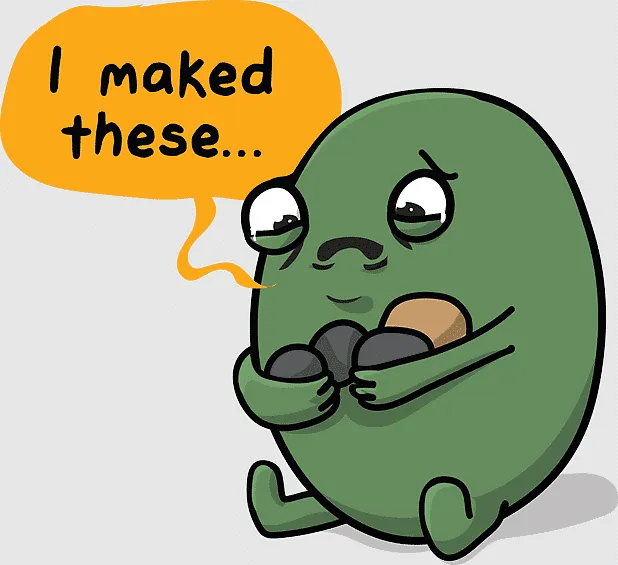

Figure 1: Anatomical location of the gallbladder (image courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic website).

Nestled comfortably within the confines of the liver, just beneath the right lobe, is a small, pear-shaped, hollow organ that quietly performs its function without needing to be told. Often discussed in our community because of the frequent occurrence of gallbladder stones, the organ is usually overlooked as a primary cause of abdominal pain until tests reveal otherwise. This is because the stomach is frequently suspected as the source of all abdominal pains, given its association with symptoms related to food intake and meal times.

The stomach is also an organ that people are more familiar with, rather than the more elusive gallbladder. It could be that people are more inclined to blame the stomach because treatment is simpler, often involving just a pill or a sip of milky alginates, instead of going to the hospital for blood tests, scans, or possibly a surgical consultation. Since gastric remedies are also widely available in local pharmacies, the public’s assumption that all their tummy woes originate from the stomach is somewhat reinforced.

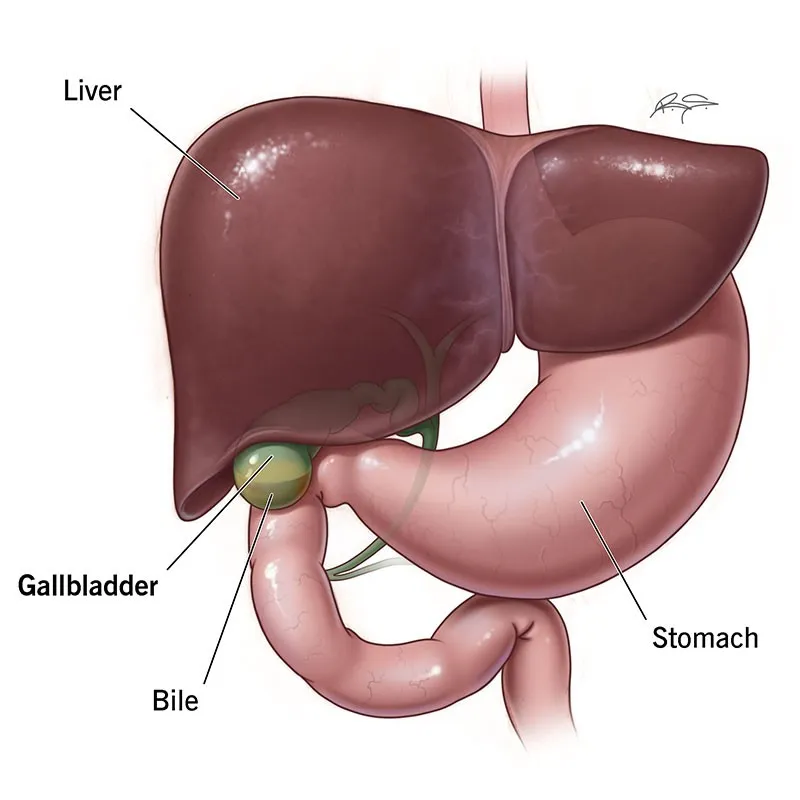

Figure 2: The gallbladder structure in relation to the cystic duct, common hepatic duct, common bile duct, and the pancreatic duct (image courtesy of the Johns Hopkins Pathology website).

Well, the gallbladder is just as important, if not more so. The organ typically measures 7 to 10 cm in length and 4 cm in width in adults, with a capacity of around 50 millilitres. Our gallbladder functions as a storage reservoir for bile. It receives bile from the liver, stores it, and then releases concentrated bile into the small intestine in controlled amounts during meals to aid fat digestion. Normally, the gallbladder shrinks after eating and fully expands during fasting. This is why doctors often advise patients to fast (nil by mouth) before an abdominal ultrasound, allowing doctors to visualise the organ more clearly.

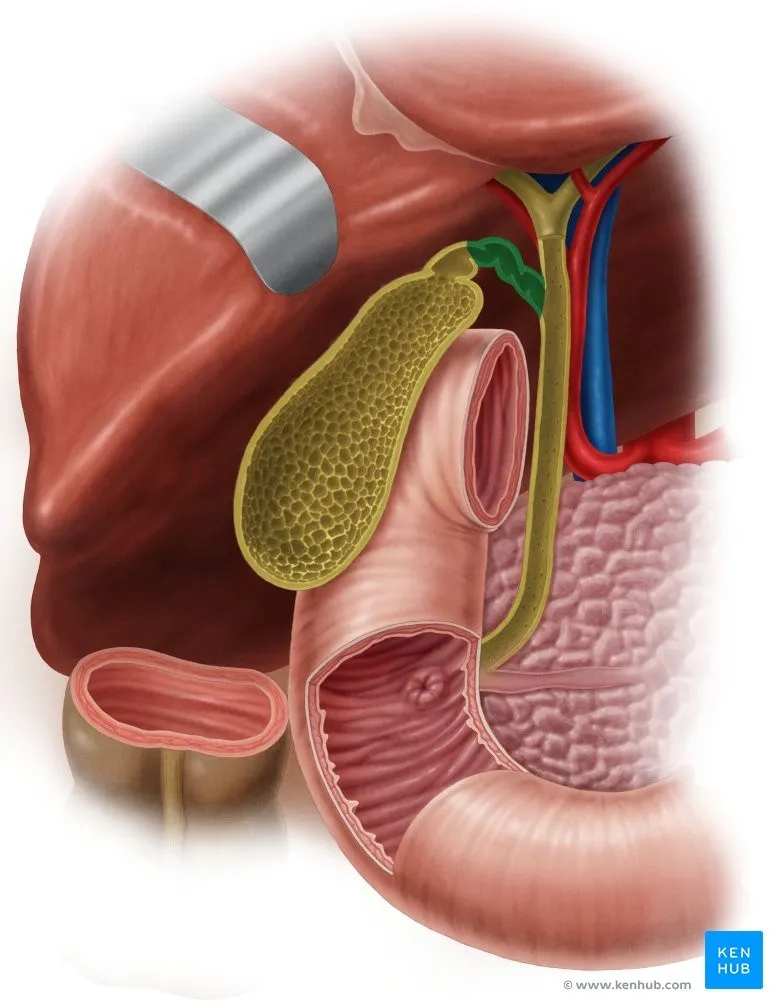

Figure 3: Exploded image of the gallbladder situated just below the right lobe of the liver, in front of the duodenum (the first segment of the small intestine), above and in front of the large bowel (shown here as the ascending colon – lower right part of this image), and near the head of the pancreas (image courtesy of www.kenhub.com).

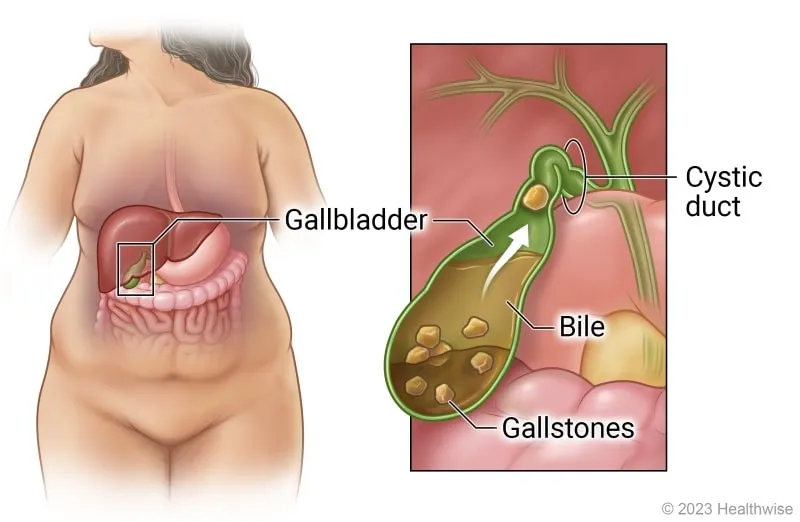

Figure 4: Cartoon illustration showing how gallstones appear within the gallbladder (image courtesy of the UK Health care website).

Gallbladder stones are perhaps the most common issue affecting the gallbladder in humans. They form when deposits of bile harden within the gallbladder. Most of the time, they rest silently in the organ without causing any symptoms or revealing their presence. Many patients live with such stones throughout their lives without knowing, often only discovering them during an annual health screening or check-up. Patients are then reassured that there is no cause for concern, encouraged to maintain an active lifestyle, and advised to moderate their diet by reducing oily, greasy, ultra-processed, and processed foods. Monitoring is only necessary if new symptoms develop.

Figure 5: Gallstones as they appear outside the human body (image courtesy of the Pace Hospitals website).

On the other hand, some patients discover their gallstones in less favourable circumstances, as was the case with our patient, Hock Soon. The most common symptoms include abdominal pain that is vague, episodic, usually lasting a few hours, and then disappearing suddenly. During such episodes of discomfort, a reasonable person would initially try over-the-counter remedies such as alginates, antacids, and even stronger ‘gastric’ medications. Occasionally, the symptoms resolve on their own, but if the pain escalates, the patient has no option but to seek advice from their GPs. Based on the circumstances and initial findings, GPs may either order additional laboratory and ultrasound tests if such facilities are available. If not, they will refer the patient to hospital specialists for further consultation.

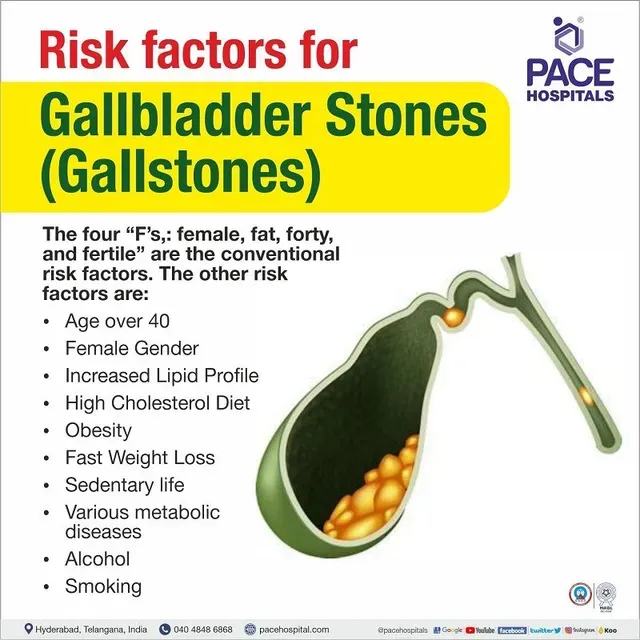

Figure 6: Summary of risk factors for gallbladder stone formation, illustrating the traditional four ‘F’s' as depicted in this cartoon (image courtesy of the PACE hospitals’ website).

Gallstones, depending on their location outside the gallbladder, can cause different types of pain, varying in severity and associated symptoms. It is helpful to understand some key terms related to how a gallstone can cause various discomforts.

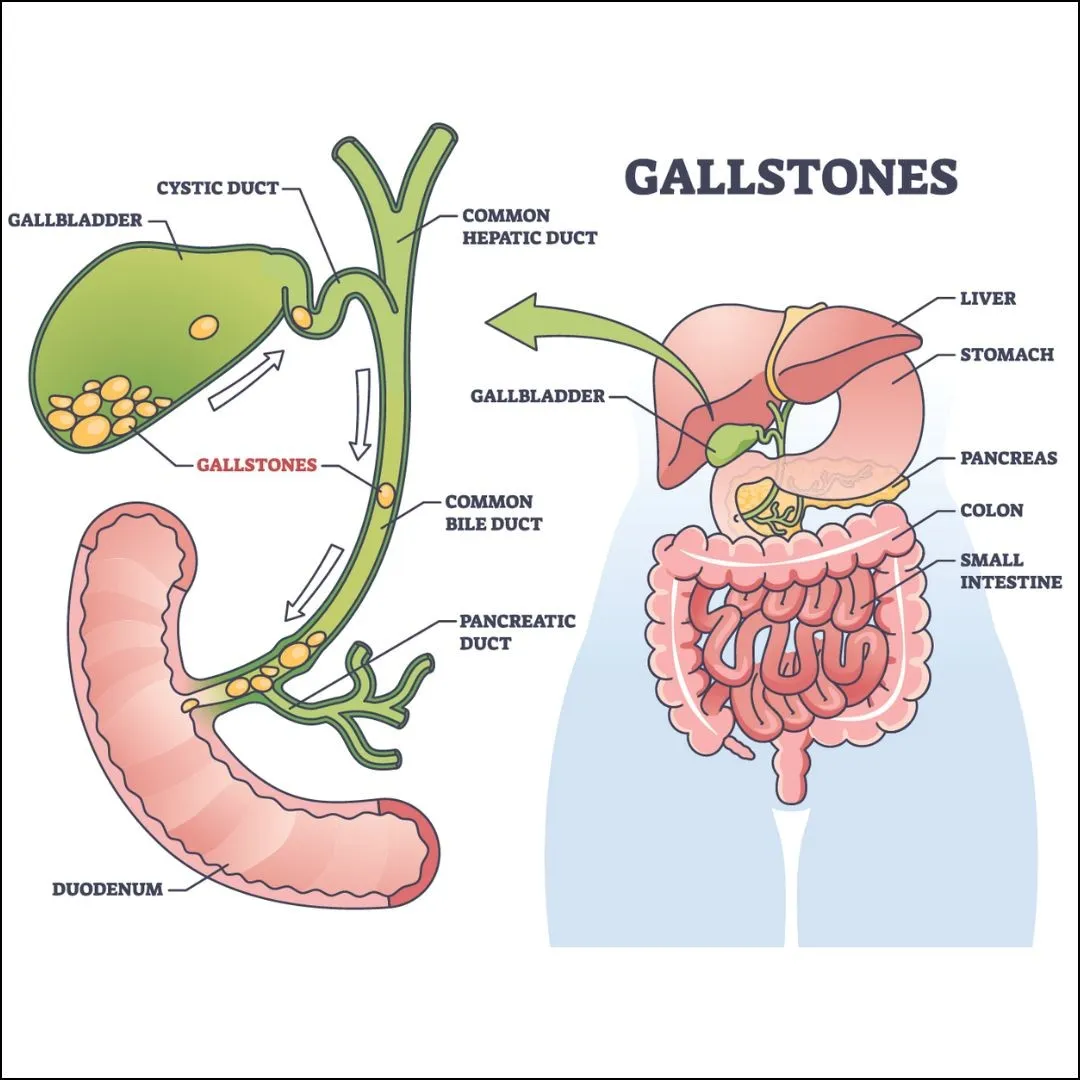

Figure 7: Pictorial representation of the various gallstone locations and the problem it gives rise to – a stone impacted within the cystic duct leads to cholecystitis, whereas stones lodged within the common bile duct are termed as choledocholithiasis (image courtesy of the Continental Hospitals website).

Biliary colic occurs when a stone becomes lodged in the cystic duct, which is the outlet of the gallbladder. Often referred to as a gallbladder attack or a gallstone attack, the pain is described as colicky—coming and going in waves due to muscular contractions of a hollow organ. It happens as the gallbladder tries to push bile past the stone. The pain is usually located in the right upper abdomen and lasts from 15 minutes to several hours. Patients often report having eaten a heavy, fatty meal just prior. If it occurs after dinner, the patient may not sleep well, leading some to seek treatment in emergency departments or clinics at night, fearing they are experiencing severe ‘gastric’ pain or a heart attack. Typically, our patient receives intramuscular or intravenous analgesics, proton pump inhibitors, and other symptomatic medications. After resting for a while, they often feel well enough to be discharged within an hour or two. Most do not return for follow-up and resume normal activities until a second or subsequent attack occurs.

Usual symptoms include a sharp, crampy, or dull ache of varying severity. The pain may radiate towards the right shoulder tip or the chest (the latter mimicking a heart attack). Patients also complain of nausea, vomiting, reduced appetite, and indigestion. The pain resolves immediately when the stone either pops straight back into the gallbladder or intensifies if it moves down into the common bile duct.

Cholecystitis occurs when gallstones become stuck or impacted within the cystic duct and refuse to move. They cannot return to the gallbladder or pass into the common bile duct. As a result, bile cannot flow out into the small bowel and begins to build up in the gallbladder. This causes the gallbladder to swell, stretching the organ's surface and irritating the pain receptors, leading to intense, persistent pain. Biliary colic then progresses into acute cholecystitis, where inflammation develops. Along with the symptoms of biliary colic, the patient now develops a fever due to infection. An additional symptom, jaundice—the yellowing of the skin—may also appear if the gallbladder inflammation encroaches on the neighbouring liver or if the cystic duct swelling impinges on the common bile duct (Mirizzi syndrome).

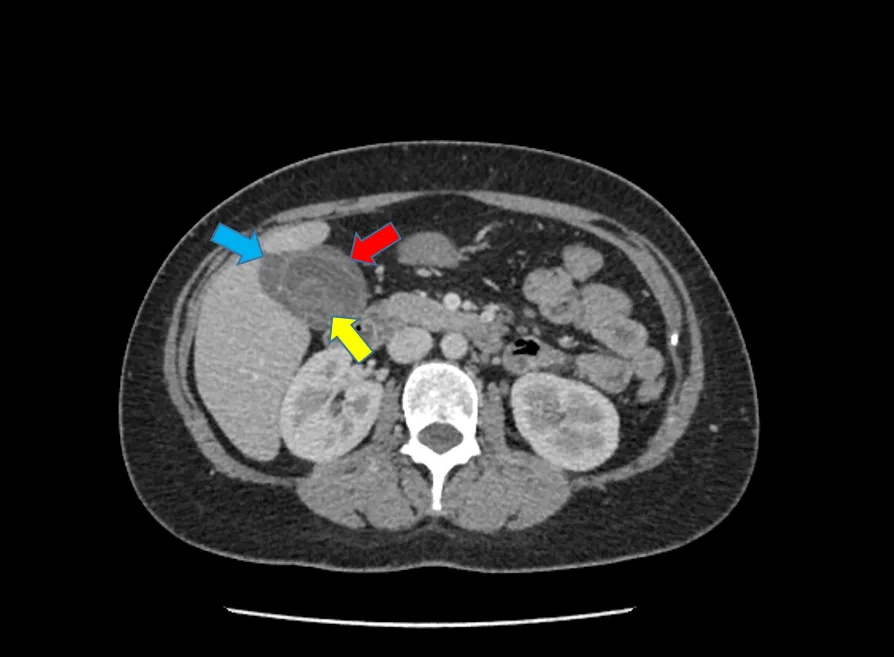

Figure 8: Cholelithiasis (gallbladder stones – yellow arrow) and cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation manifested by thickened gallbladder wall – red arrow, and inflammatory fluid surrounding the gallbladder – blue arrow).

Acute cholecystitis is a condition that requires prompt medical attention and often necessitates hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, fluids to correct dehydration, and symptomatic medications for nausea and vomiting. Blood tests are useful to assess the severity of liver function abnormalities, infective panel results, and blood cultures, which guide antibiotic selection. Patients should expect imaging procedures, such as an ultrasound and/or a CT scan, as a foundation to establish the diagnosis and evaluate the severity and complications of acute cholecystitis. These tests provide comprehensive clinical and diagnostic information to help doctors better understand your condition and discuss with you the potential need for surgery and its timing, when indicated.

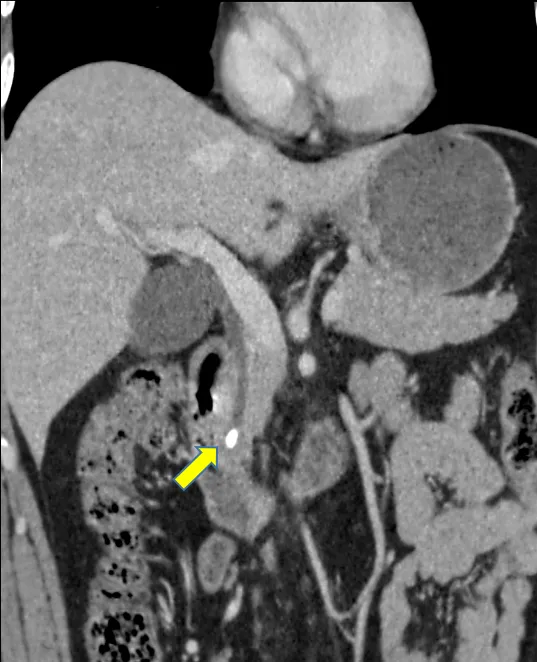

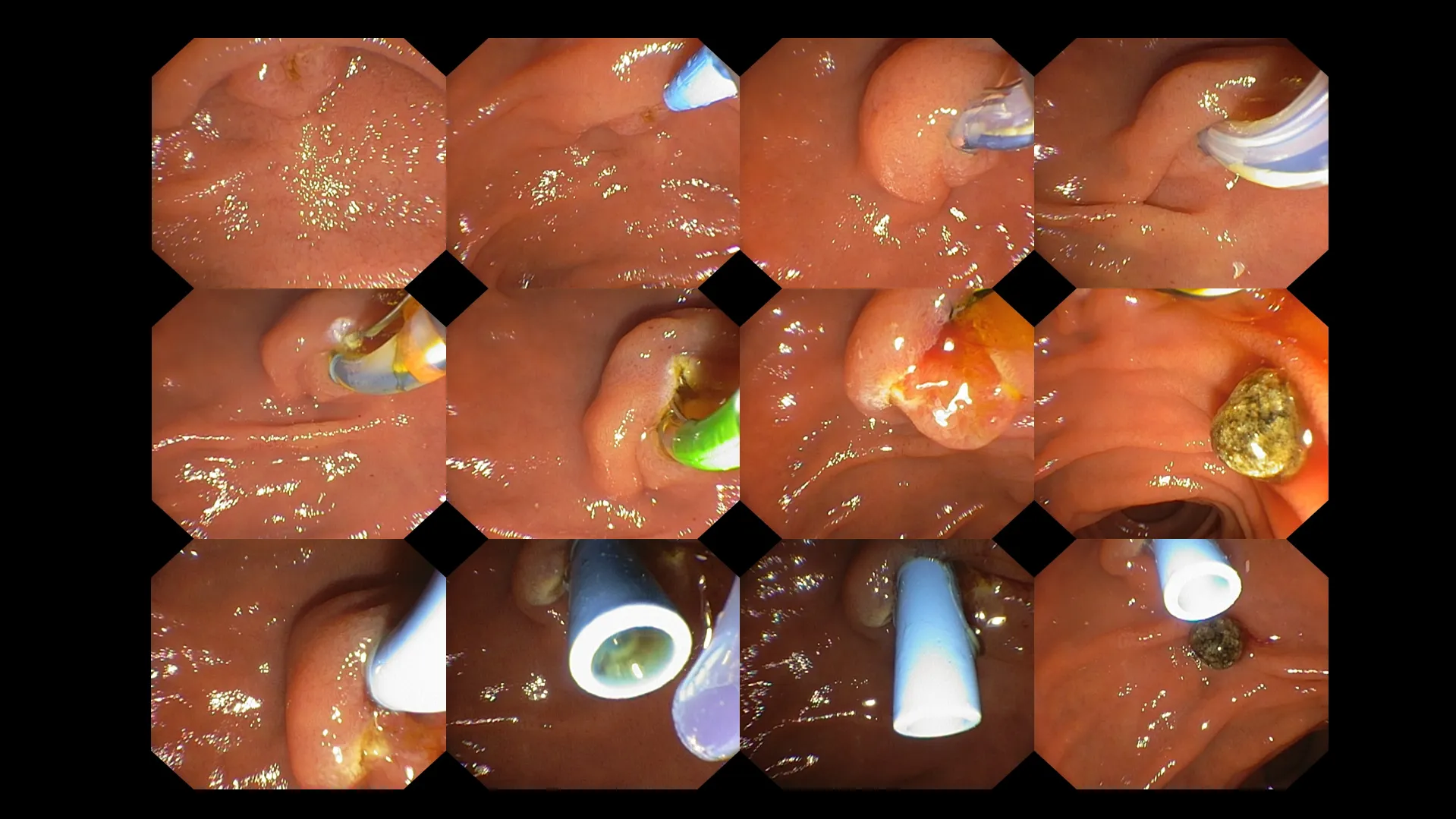

Choledocholithiasis and cholangitis – the term 'choledocholithiasis' refers to when the gallstone(s) move further down the cystic duct and fall into the common bile duct, becoming lodged at the end of the duct and causing a blockage of bile flow. Such situations lead to bile stagnation, which promotes infection and, over time, causes bile duct swelling and backflow of bile into the liver. Without prompt treatment, patients are likely to develop cholangitis – inflammation of the bile duct – and, in severe cases, septicemia, where the infection spreads into the bloodstream, potentially becoming life-threatening. Hospital admission becomes necessary not only to initiate life-saving measures for conditions like acute cholecystitis but also to facilitate a timely procedure to decompress the bile duct by placing a plastic tube to restore bile flow. This stent placement is performed through an endoscopic procedure called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (or ERCP).

Figure 9: Choledocholithiasis (gallbladder stone within the common bile duct – yellow arrow).

Figure 10: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed on a patient with an impacted gallbladder stone within the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis). A step-by-step approach is used to identify the doorway into the common bile duct, followed by the insertion of a catheter loaded with a guidewire into the biliary pathway. The doorway (ampulla) is then slightly cut to permit stone retrieval. Following the success of stone extraction, a temporary stent (blue tube, seen in the last row of the image above) is placed to decompress the biliary tree, allowing for the free passage of bile flow.

Patients with cholangitis often stay in the hospital for a few days to monitor their response to antibiotics, wait for final blood or bile culture results for targeted antibiotic therapy, perform serial laboratory tests to evaluate their overall clinical and biochemical response, and watch for potential complications following ERCP. The duration of hospital stay is determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the severity of the patient’s condition.

Figure 11: Another example with enclosed CT scan images. Gallbladder stones (yellow arrow) and an impacted stone within the common bile duct (red arrow) are visible on the CT scan. Endoscopic image of the ampulla (blue arrow). Step-by-step identification of the ampullary orifice, cannulation with a guidewire, and stent placement to facilitate bile passage.

Figure 12: Suppurative (purulent) cholangitis secondary to obstructed bile ducts – the trail of milky liquid is pus resulting from bacterial infection caused by prolonged stone obstruction of the common bile duct. The voluminous pus flow was abrupt following successful cannulation of the ampulla.

The next concern is unavoidable. Well-informed patients often know what to expect next. The doctor may have successfully treated the acute condition by giving painkillers for biliary colic, antibiotics for acute cholecystitis, performing an ERCP with stone removal and stent placement for choledocholithiasis, and prescribing antibiotics for acute cholangitis, but is that all? The ongoing question is whether surgery is truly necessary. Is gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy) via open surgery, laparoscopic (keyhole), or nowadays, robotic-assisted surgery, indicated? Instead of focusing solely on the technique, the main issue is whether the procedure should be done at all. This is a complex topic, and not everyone will have the same outcome. The obvious scenarios leading to surgery involves patients who, despite all of the above, continue to suffer the following:-

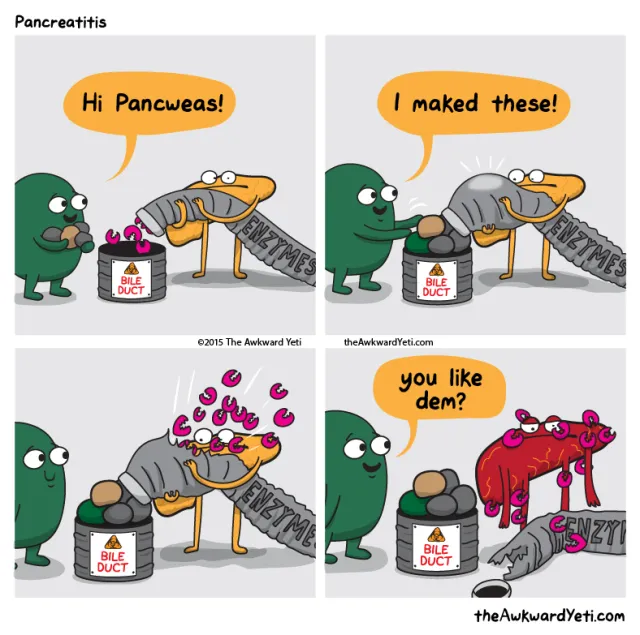

Figure 13: While a bile duct stone may block the common bile duct, it can also cause obstruction of the pancreatic duct either directly through ductal blockage or indirectly via an inflammatory response – tissue swelling leading to external compression of the pancreatic duct. This comic strip demonstrates how the gallbladder discards its stones into the bile duct, resulting in an obstructed pancreatic duct and subsequent pancreatitis caused by the corrosive pancreatic enzymes (image courtesy of the AwkwardYeti.com website).

The idea of surgery often worries patients because no one enjoys the thought of going under the knife. Your doctor will be able to explain the various reasons that might necessitate a cholecystectomy, the optimal timing for the procedure, the complications that could arise based on the technique used, and what to expect after the surgery.

I often receive questions on whether a person can live without their gallbladder. Like the appendix, its removal does not affect a patient's normal and healthy life. The liver will continue to produce bile, so you would still be able to digest fats from a greasy meal.

The only difference now is that you no longer have a gallbladder to store and concentrate your bile. You also lose the ability to regulate the amount of bile secreted depending on food intake. Instead, bile from the liver flows freely into the small bowel rather than being released in squirts or bursts. As a result, some patients may experience diarrhoea and excessive gas or bloating after consuming fatty foods. The diarrhoea occurs due to continuous, less concentrated bile, which can irritate the bowels and act like a laxative, leading to bile-acid diarrhoea. Bloating happens because of disrupted fat digestion, which also stems from the same principle of less concentrated bile.

Figure 14: The primary function of the gallbladder as described by the liver and the gallbladder’s extracurricular activities (image courtesy of the AwkwardYeti.com website)

So I’ve had my gallbladder removed. What’s next? How can I ensure that my condition is optimised?

Instead of having traditional large meals, opt for smaller, more frequent ones. This helps your digestive system process fats and nutrients more efficiently, reducing the risk of bloating and discomfort.

Many believe you must avoid fats entirely, but that’s a misconception. The body still needs healthy fats for energy, cell function, and vitamin absorption. However, since bile is no longer released in concentrated bursts, it’s sensible to:

Some individuals find that certain foods—particularly those high in fat or spice—may cause discomfort or diarrhoea after surgery. Introduce these foods gradually to assess your personal tolerance. Everyone is different, with each person having their own threshold. Do not be afraid to experiment with different foods to see how your body reacts.

Gradually increasing your intake of soluble fibre (found in oats, apples, carrots, and beans) can help normalise bowel movements and prevent diarrhoea. However, increasing fibre too quickly may cause wind or bloating, so it's best to introduce it gradually.

Drinking plenty of water supports digestion and helps prevent constipation, which can sometimes occur after surgery.

Some people experience temporary lactose intolerance after gallbladder surgery. If you notice digestive discomfort with dairy products, try lactose-free options or reduce intake until your system adjusts.

Most people can eventually enjoy moderate amounts of fat. Start slowly and pay attention to your body's response.

Enzyme supplements are usually unnecessary. Your body typically adapts, but if you experience ongoing difficulty, your doctor may recommend specific treatments.

Yes, but as with any surgery, discuss your plans with your healthcare provider to ensure the best possible outcome.

No foods are absolutely forbidden, but moderation is key. Focus on a balanced, nutrient-rich diet.

Living without a gallbladder is entirely possible, and most people find they can return to a normal diet and lifestyle within a few months after surgery. While some temporary adjustments to eating habits may be necessary, your body is remarkably adaptable. Emphasising smaller meals, healthy fats, and fibre, while listening to your body’s cues, can help you enjoy life to the fullest. Should you experience persistent or severe symptoms, consult with your healthcare provider for guidance and support.