I feel bloated, doctor. My tummy feels like a drum.

This is the most common statement I encounter daily as a practising gastroenterologist in a private hospital in Penang. Even when talking to friends and relatives during my days off, they often sit beside me casually and ask if I can listen to their digestive complaints. I can usually guess it is one of three things: a painful tummy, a bloated abdomen, or nagging heartburn. As much as I enjoy friendly banter, the conversation often quickly shifts to something more serious.

In technical terms, bloating is a subjective sensation of tummy distension, swelling, or fullness felt when the abdominal wall becomes tense and sometimes firm. It does not cause severe, debilitating pain that would drive someone to the emergency department for immediate relief and further assessment, but it is uncomfortable enough to prompt medical consultation. It affects a patient’s quality of life, as they cannot enjoy a full meal, often feeling nauseated, sometimes even vomiting. When it occurs at night, sleep can be disrupted due to the heaviness in the belly. Bloating may result from excess gas, fluids, fecal matter, a solid tumor, or even a pregnancy (undiagnosed). It remains a bit of a mystery when a patient of different age, ethnicity, gender, and body type seeks relief for their ‘bloatedness’.

Figure 1: Bloating is a subjective complaint that necessitates further medical assessment if the symptoms become persistent and troublesome (image courtesy of Alpine Surgical).

While it can be confusing at times, it can also be quite fascinating to help the patient unravel the complex array of symptoms and then provide the right solution to support them. It becomes even more rewarding when they return to tell you that their bloating, which has troubled them for weeks, months, years, and even decades, is now a thing of the past. Although I would like to focus on ‘gastroenterology bloating’ or bloating caused purely by gastroenterological disorders, this is not always the case. Patients often find it difficult to differentiate between symptoms and their underlying causes. Therefore, clinicians must be alert to potential pitfalls and red herrings when taking a detailed history and examining patients with bloating.

What should you expect when visiting a clinician’s office for bloatedness? Or how should you prepare for your consultation with your gastroenterologist? I understand that feeling anxious about the unknown and the fear that the news may be unfavorable is common. There may also be concerns about the numerous tests your doctor might suggest. Writing down your thoughts and organizing your chief complaints in a chronological order can help; your clinician will guide you through your concerns. We aim to demystify the events leading to your bloatedness, identify the cause, and provide an appropriate solution for your ailments.

Here’s some personal sharing…

Since starting private practice in Penang, I have grown and learned from the challenges and the difficult task of understanding bloating. I have encountered multiple causes of bloating unrelated to gastroenterology, including a large ovarian tumor/cyst in a teenage girl, significant uterine fibroids in a middle-aged woman, impacted kidney stones in an obese man, undiagnosed kidney failure in a thin elderly gentleman, heart failure with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in a portly lady, a liver abscess in a young travelling businessman, a massive liver tumor in an elderly man, an enlarged spleen caused by a blood-related disorder in a young woman, pancreatic cysts, perimenopausal symptoms, and three cases of undiagnosed and unexpected pregnancies.

Such a diagnosis can imitate bloating caused by gastroenterological issues to the extent that patients might seek over-the-counter remedies like antacids, alginates (Gaviscon), and simethicone (e.g., Maalox Plus, Alucid, Gas-X, and GazGo) for relief. Conversely, some, influenced by experiences shared by family or friends, may start experimenting with traditional medications, supplements, prebiotics, probiotics, and proton pump inhibitors (acid-neutralizing agents) for an indefinite period without seeing any improvement. This delay in diagnosis can be an issue later if it turns out to be a malignant cause.

I hope that this column will serve as an aid to inform the public that, should there be doubts, always consult your general practitioner or obtain a referral to see a specialist if your symptoms persist.

Now let us focus on the core issue of bloating caused by gastroenterological factors. This is a systematic and non-exhaustive list of causes, which I find useful in a busy clinic setting. I prefer to write this article from a first-hand perspective when I see a patient:

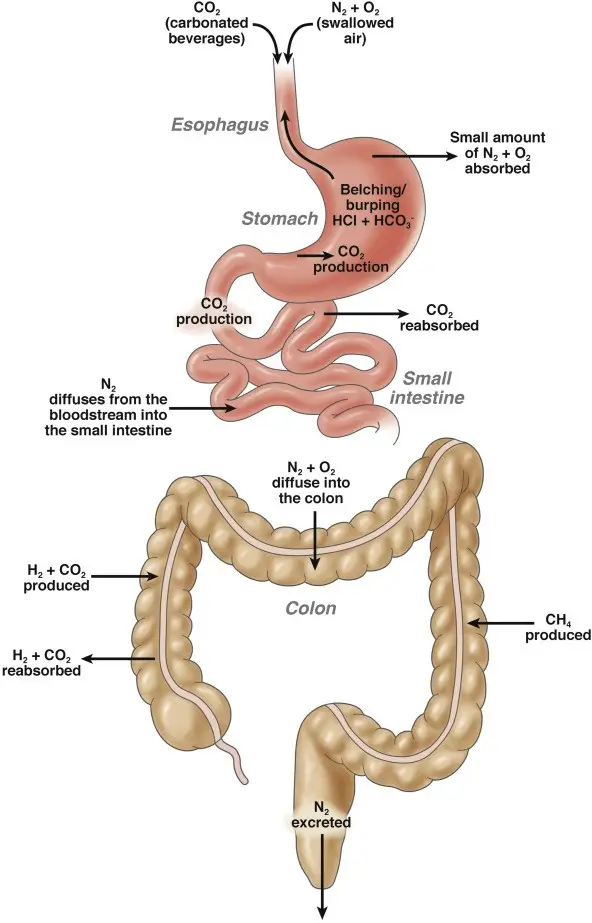

Figure 2: The gut efficiently balances the production, reabsorption, and excretion of gaseous matter. This delicate process involves many key players, much like an orchestra is conducted. Any disruption to these mechanics, in any form, results in either excessive gas production, reduced gas reabsorption and elimination, and thus causes bloating (image courtesy of Lacy et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021).

Figure 3: Image depicting the Helicobacter pylori bacterium colonizing the stomach wall and over time leading to chronic inflammation, stomach ulcers, and cancers (image courtesy of the RACGP website).

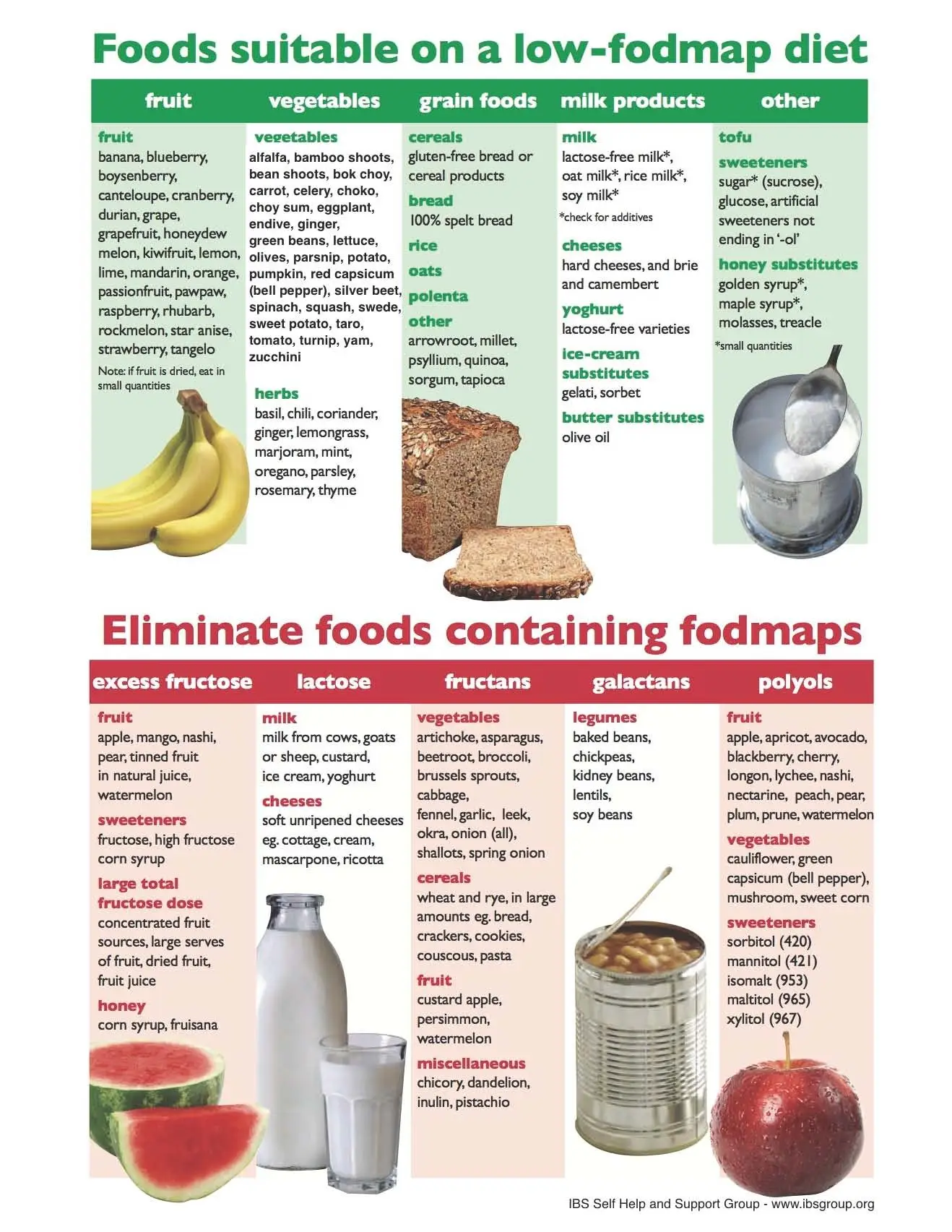

Figure 4: A common chart displaying categories of low and high-FODMAP diets. It is advisable and possibly important to consult a gastroenterologist and a dietitian before starting such a dietary approach. Beyond trying to follow this diet yourself, it is necessary to understand how and when to reintroduce these foods after a period of food group elimination. A low FODMAP diet is not intended to be followed strictly for a long time, as it does not provide sufficient nutrition (image courtesy of the Gastroenterology Associates of New Jersey website).

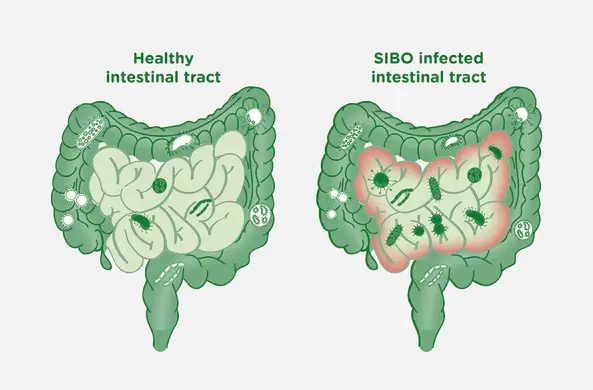

Figure 5: I enjoy showing this diagram to patients suffering from SIBO – it illustrates an overgrowth of microbes within the small bowel. The small intestines are a pristine environment, with a continuous sweeping motion (peristalsis) that maintains its cleanliness. Motility issues affecting this peristalsis can understandably disrupt the cleaning process and promote the overgrowth of bacteria, leading to SIBO. The ‘bad’ bacteria that have established a foothold in your small bowel will begin to thrive and produce foul gases, causing abdominal distension and bloating (image courtesy of the BioKPlus Canada website).

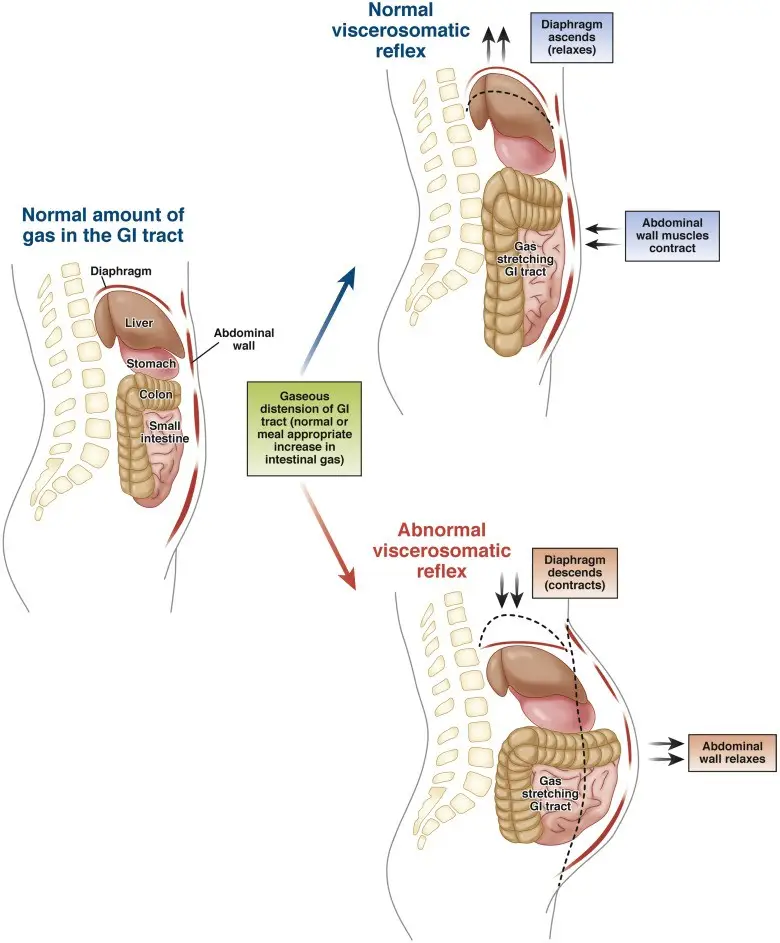

Figure 6: One proposed mechanism in functional bloating involves poor coordination between the diaphragmatic muscles and the abdominal wall muscles. In a healthy individual, the body responds to increased gas by relaxing the diaphragm and contracting the abdominal wall muscles. This mechanism helps distribute the gas evenly, preventing abdominal swelling. However, in patients with functional bloating, these reflexes are not properly activated – the diaphragm contracts, and the abdominal wall musculature relaxes, resulting in significant bloating and protrusion of the abdominal wall (image courtesy of Lacy et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021).

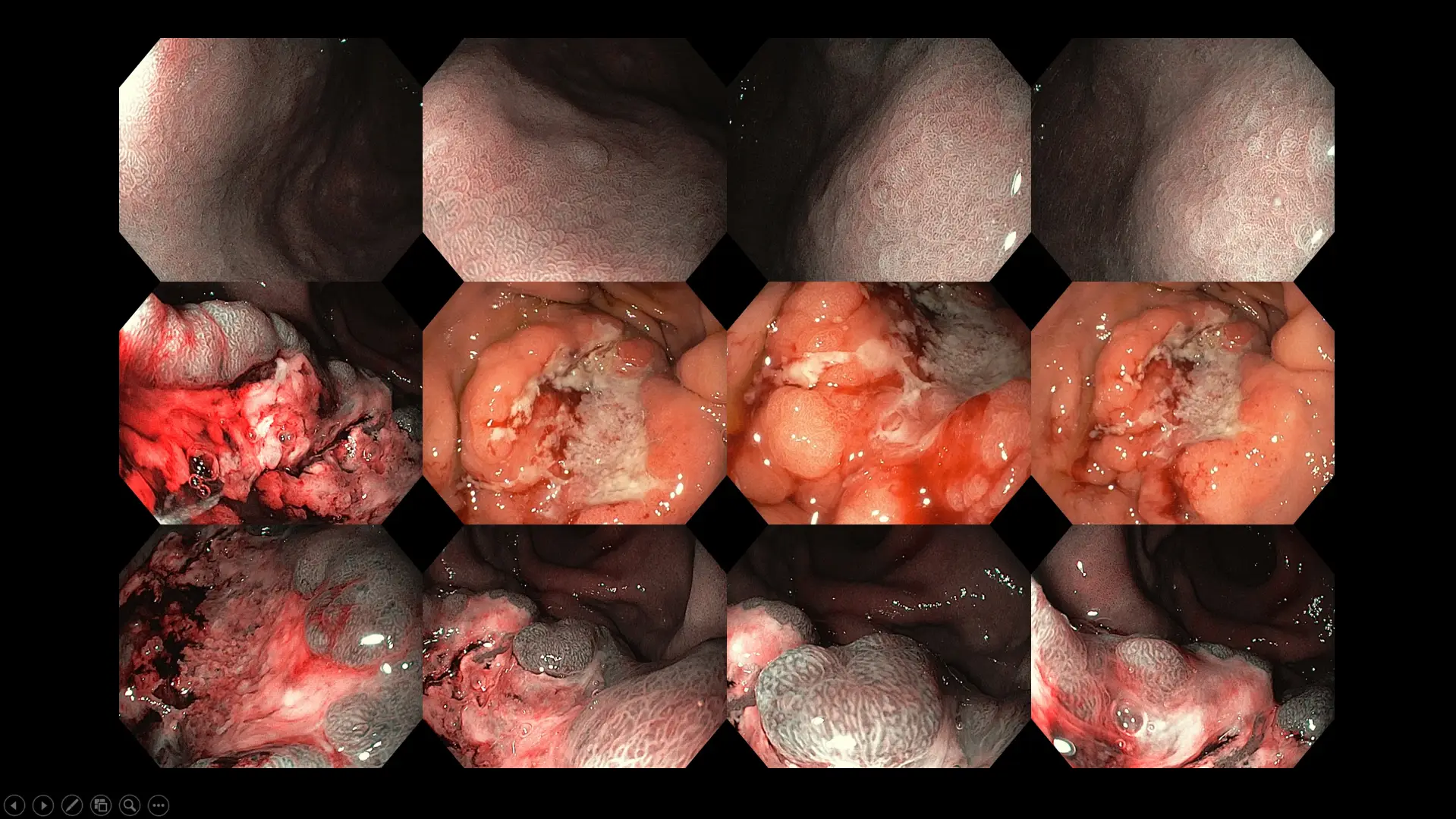

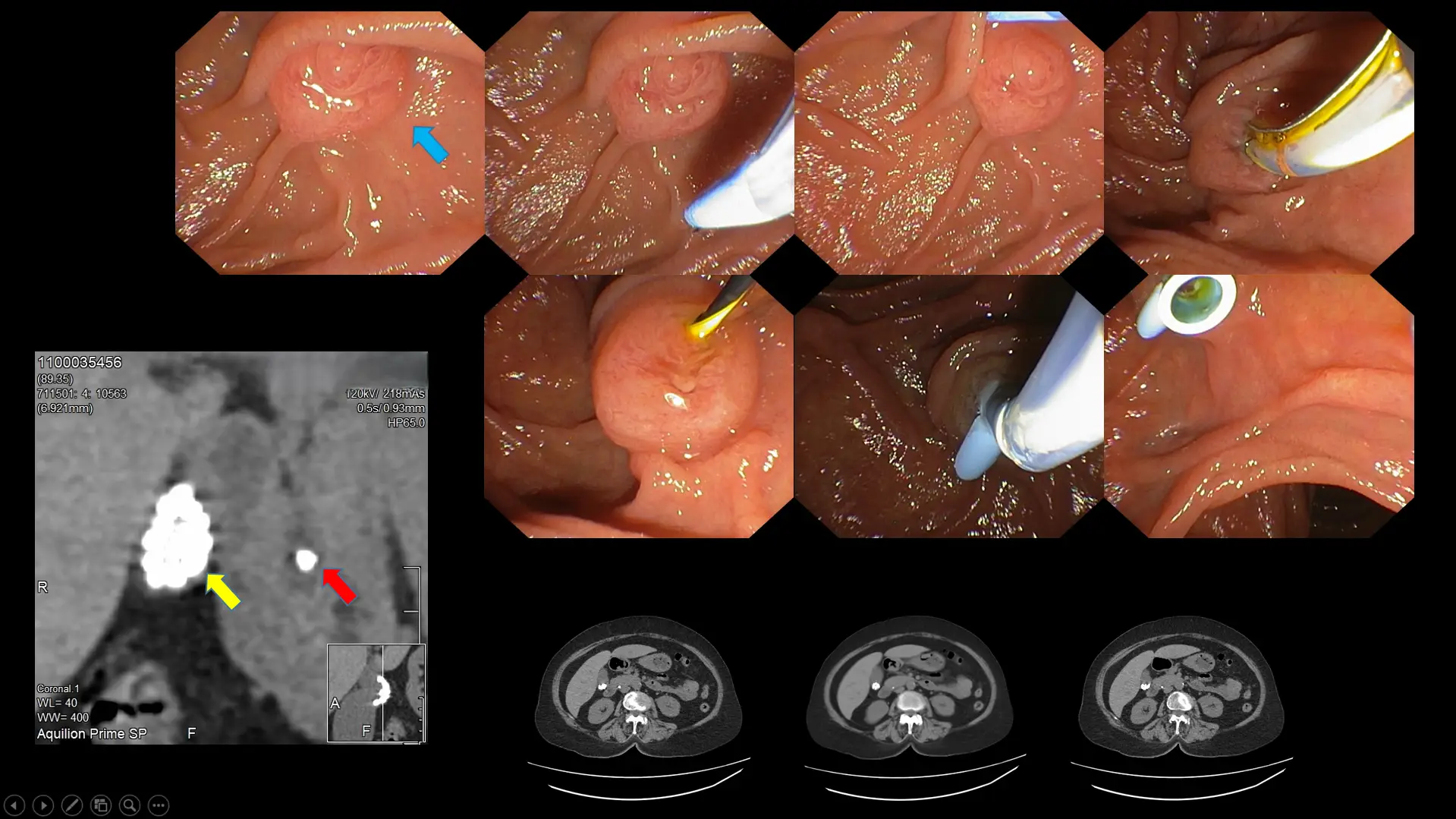

Figure 7: Case of advanced stomach cancer with Helicobacter pylori infection as background – the patient presented with bloatedness, abdominal discomfort, early satiety, loss of appetite, and weight loss over three months before seeking treatment.

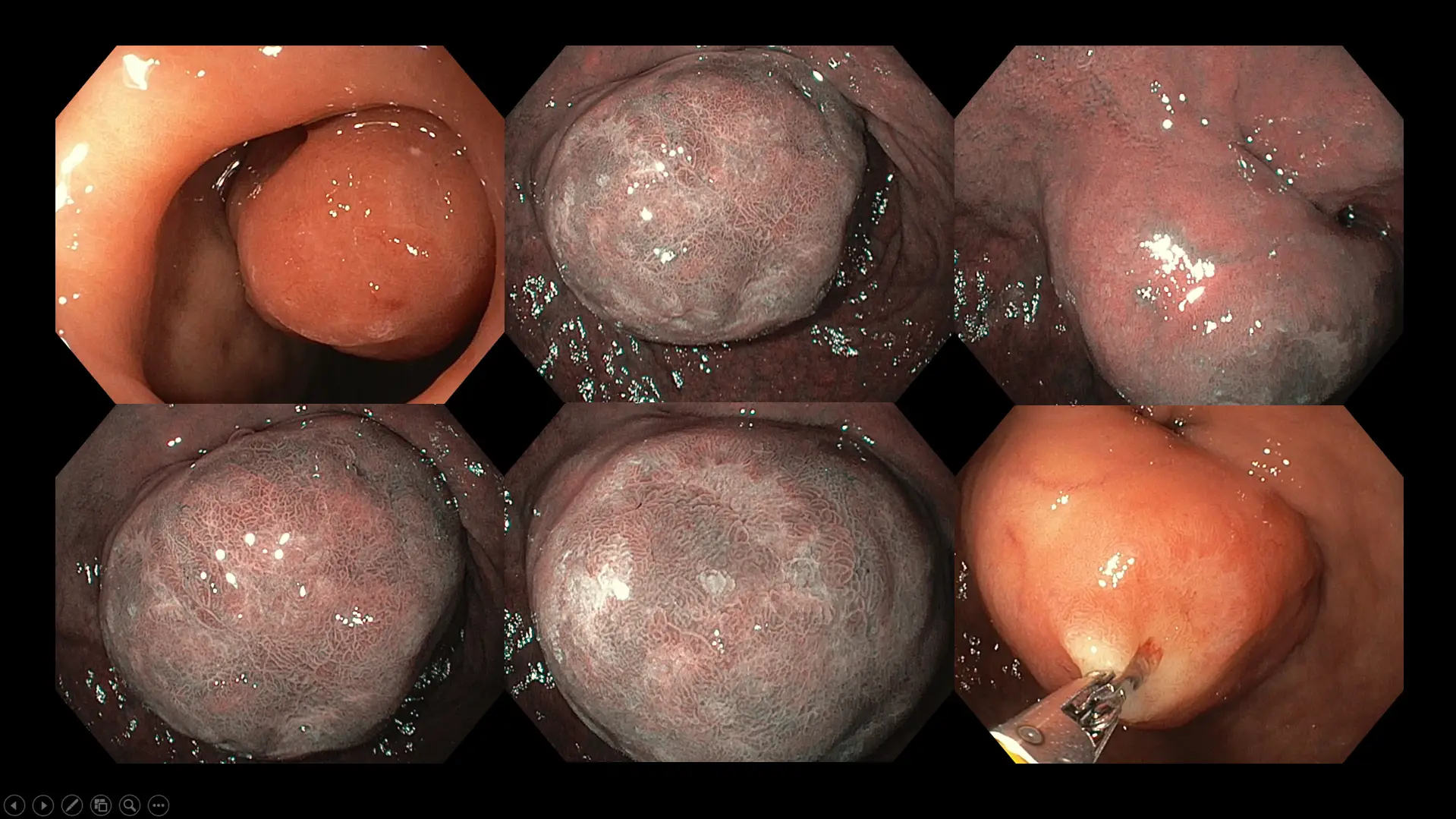

Figure 8: Case of a large duodenal (first part of the small bowel) tumor in a patient with long-standing abdominal fullness, bloating, and mild crampy discomfort. Although surgical removal was offered due to the size of the polyp, our patient chose a conservative watch-and-wait approach because of her advanced age and multiple medical conditions.

Figure 9: Case of an advanced left-sided colon cancer in a patient who experienced new-onset constipation and bloatedness for six months before consulting a doctor.

Figure 10: A case illustrating diverticular disease of the large bowel with impacted stools. Our patient experienced frequent abdominal cramps hours after a heavy meal, along with bloating and constipation. Note the varying sizes of the diverticular orifice, which range from as small as 1 mm in some patients to as large as 10 cm in extreme cases.

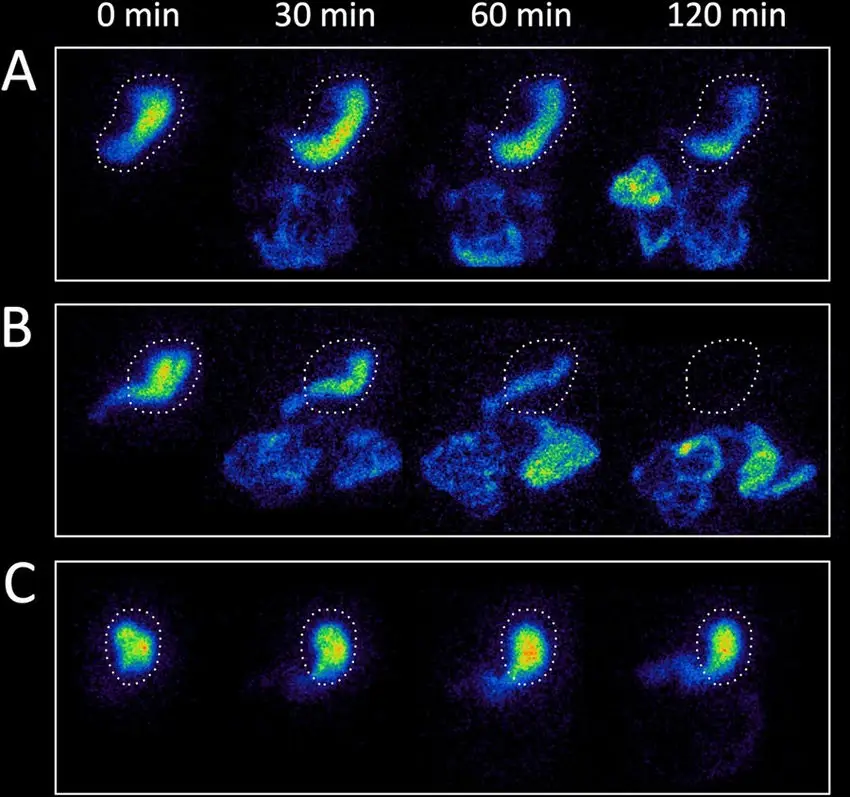

Figure 11: A panel of gastric emptying time scintigraphy images in three patients – (A) a healthy individual with normal stomach emptying time, (B) a patient with rapid gastric emptying following medication, (C) a patient with delayed gastric emptying. A normal stomach empties 60% of its content by 2 hours and 90% by 4 hours. Patients with delayed gastric emptying have gastroparesis, which can be caused by infection, previous stomach surgeries that damage the vagal nerve, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus affecting the autonomic nerve function supplying the stomach, as well as certain neurological and autoimmune disorders, and in some cases, it is idiopathic (unknown) (image courtesy of Borghammer et al. NPJ Parkinson’s Disease 2017).

Figure 12: An example of a patient with long-standing gallbladder inflammation caused by gallbladder stones (yellow arrow). One of the stones fell out and became lodged in the bile duct (red arrow), leading to infection and severe, debilitating pain due to obstruction of bile flow into the small bowel (the blue arrow indicates the opening of the bile duct into the small bowel). A timely procedure, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), was performed to restore bile duct flow by inserting a plastic tube through that opening.

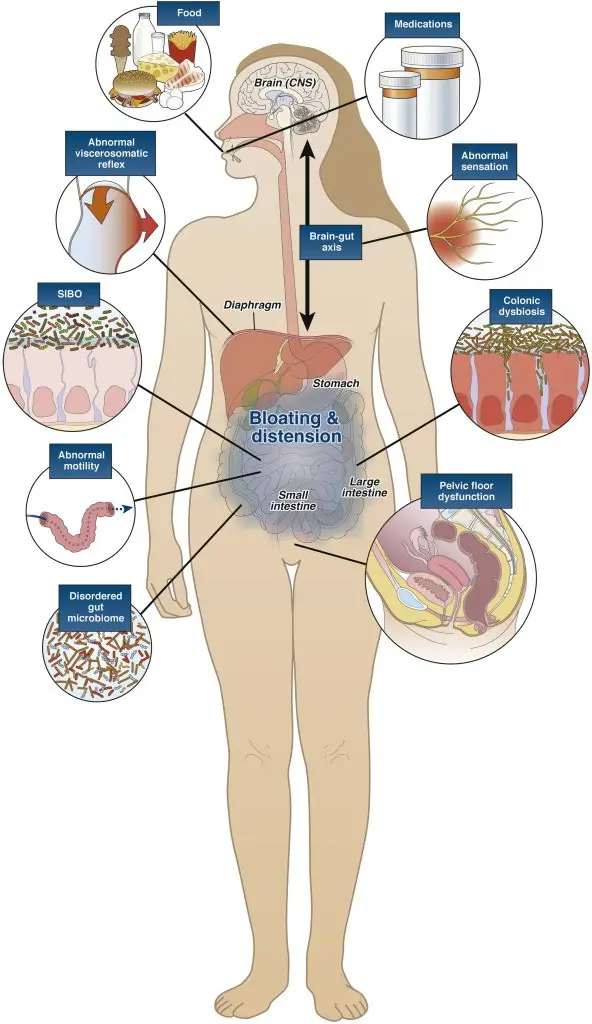

Figure 13: Cartoon illustration summarizing the various functional causes of gassiness and bloating, the most common of which are food and medications, previous gastrointestinal infection, disordered gut motility, bacterial overgrowth leading to gut dysbiosis, heightened perception of pain and gas from disorders of the gut-brain axis, and abdominal muscle wall and diaphragm discordance (image courtesy of Lacy et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021).

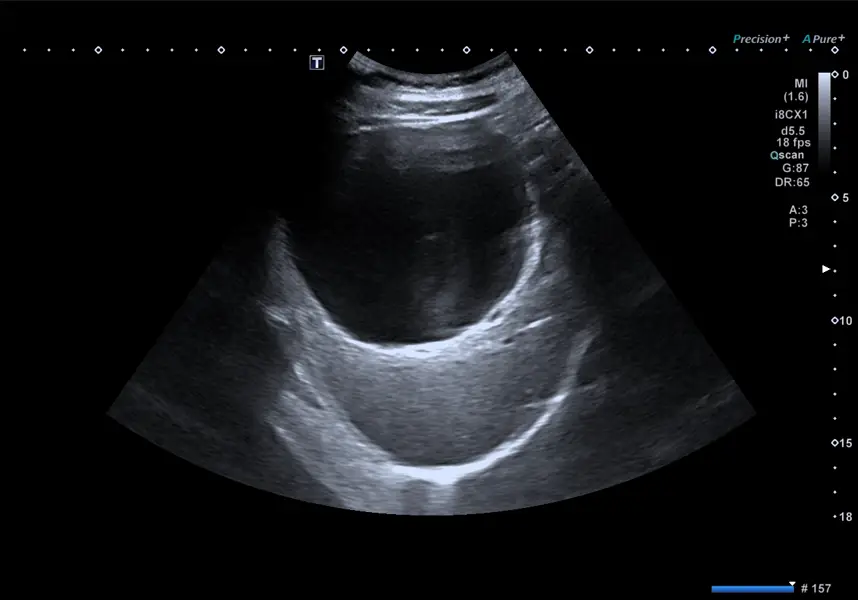

Investigations into bloating are based on the presumed diagnosis and likely cause, but typically involve an abdominal and pelvic ultrasound along with routine blood tests. Occasionally, a CT scan may be chosen over an ultrasound as the initial investigation if the history and clinical examination clearly indicate a disorder best assessed with a CT, or if the patient presents with constitutional symptoms or red flags such as significant appetite loss and unintentional weight loss over a short period. These signs may suggest the possibility of an underlying malignancy. An upper endoscopy and colonoscopy are also performed if a digestive cause is suspected, especially when the patient exhibits other high-risk symptoms such as passing blood, vomiting blood, persistent abdominal discomfort or pain, or a recent change in bowel habits.

Figure 14: An abdominal ultrasound shows a large liver cyst in a patient experiencing early satiety, epigastric discomfort, and bloating. Ultrasonography is a useful initial diagnostic tool in most cases due to its safety, lack of radiation, widespread availability, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness.

Figure 15: CT scans are useful when a detailed assessment is needed to evaluate a known or suspected pathology where an ultrasound is insufficient. CT scans can also be used as the primary modality for suspected malignancy or if surgery might be required later. The figure above shows an abdominal and pelvic CT scan revealing a large benign ovarian tumor in a patient presenting with abdominal fullness, swelling, bloating, and reduced appetite.

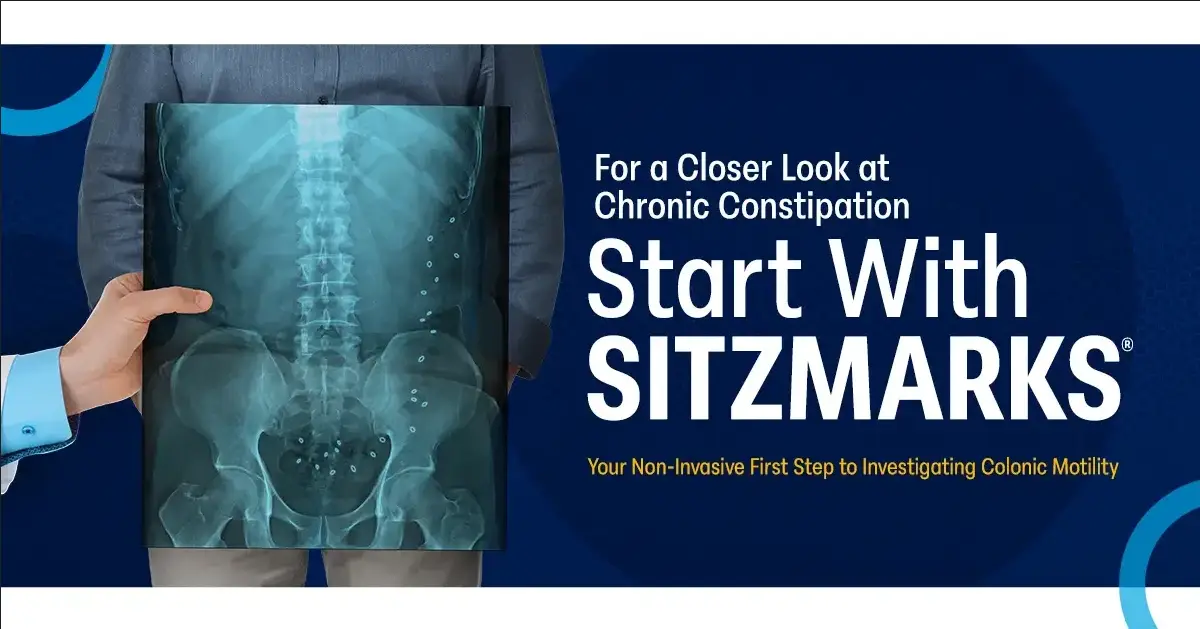

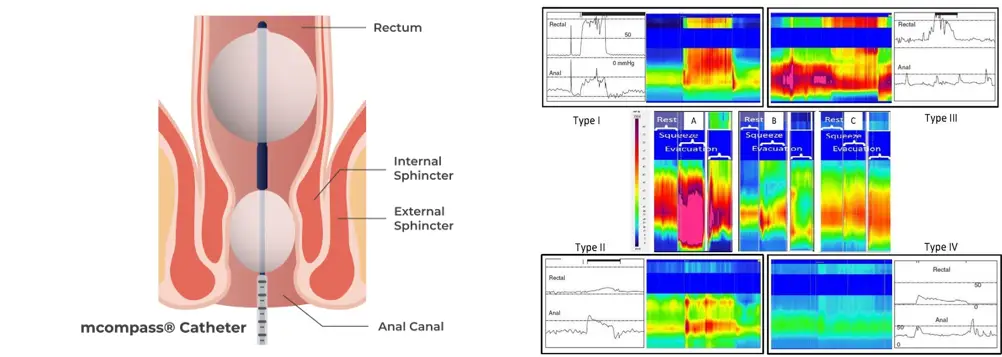

Non-invasive tests are reserved for patients who do not exhibit red flag symptoms and are chosen based on the possible underlying cause. The urea breath test, for instance, helps diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection. Conversely, the hydrogen or lactulose breath test is used for patients suspected of having small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or carbohydrate malabsorption. More advanced tests to investigate motility disorders include an esophageal high-resolution manometry to identify esophageal abnormalities, a gastric emptying study using nuclear scintigraphy with a gamma camera to detect gastroparesis (see Figure 11), a colonic transit study with a Sitzmarks capsule and several abdominal X-rays to evaluate the transit time of the large bowel, and anorectal studies employing high-resolution anorectal manometry to assess the function of the anal and rectal muscles.

Figure 16: The Sitzmarks capsule study is a practical, safe, and cost-effective tool to assess constipation subtypes – colonic motility issues (slow-transit constipation) or anorectal muscular dysfunction (dyssynergic defecation). After swallowing the capsule, an abdominal X-ray is taken after five days to examine the number of rings remaining and their distribution (image courtesy of the Sitzmarks.com website).

Figure 17: Image illustrating how anorectal manometry is performed (left) and the data analysis afterwards (right). Such assessments enable the clinician to identify the subtype of constipation caused by discoordination between the rectum and anal muscles, thereby guiding the most appropriate treatment options (image courtesy of the Medspira website and Lee et al. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2018).

The underlying cause determines the key management principles, and as we can all appreciate and learn from this article, the causes of bloating are numerous. The journey to unravel the problem is like navigating through a minefield, fraught with potential pitfalls (non-gastroenterological causes). The investigation of choice may not always rely on a single gold-standard tool but often involves a combination of tests to support and confirm the diagnosis. Your doctor will work with you to identify the root cause, which may take time, possibly requiring several clinic sessions and follow-ups. Ultimately, it is worth the patience and effort because bloating is never a pleasant experience, and a prompt, effective solution is greatly appreciated.

In summary, if you are experiencing troubling symptoms of bloating and are unsure of the cause, please visit your nearest doctor’s clinic to get it sorted. Sometimes, a little concern is more valuable than dismissing it. Finally, allow me to share a take-home message – gas may float, but it is not the only one that makes you bloat.